Virality is one of the most fascinating subjects in marketing and communication. What makes some stories and phenomena seem unstoppable, while others – just as interesting, and often more important – step out of the front door of an organization and just die on the doorstep?

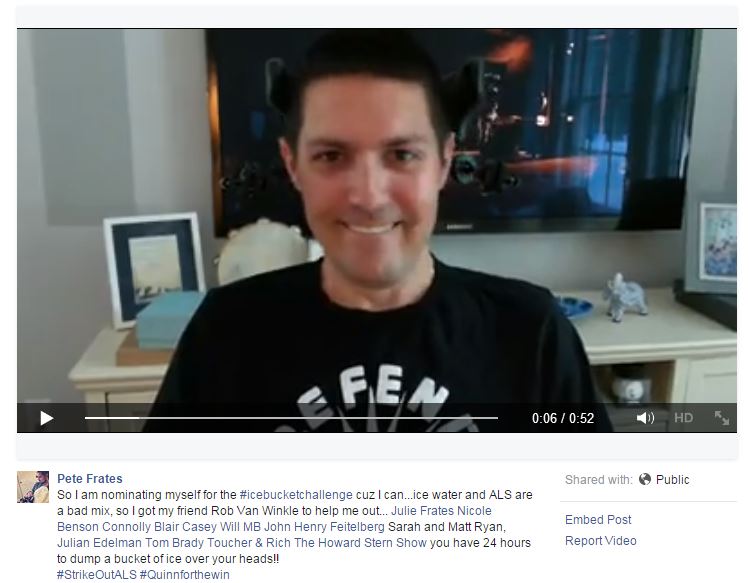

It was the subject of endless debate a few years ago, when the Ice Bucket Challenge swept the globe.

In ‘Six Degrees. The Science of a Connected Age’, Duncan Watts tries to formulate answers using network theory.

Some of the findings have immediate implications for every marketing and communication professional.

Viral hypes are “information cascades”

Take the Ice Bucket Challenge, one of the biggest viral phenomena of the last decade. The Ice Bucket Challenge, says Watts, is the same phenomenon that occurs when you’re at a concert, and all of a sudden everybody starts clapping in the same rhythm. It’s also quite similar to the way crickets somehow seem to chirp synchronously, he says, and it’s called an “information cascade”:

During such an event, individuals in a population essentially stop behaving like individuals and start to act more like a coherent mass.

Duncan Watts

What is fascinating about information cascades is that, once they begin, they are virtually unstoppable.

What all information cascades have in common, however, is that once one commences, it becomes self-perpetuating; that is, it picks up new adherents largely on the strength of having attracted previous ones.

Duncan Watts

This is the reason why media were so fascinated – no, hooked on the Ice Bucket Challenge: it just wouldn’t stop. Journalists wanted to know: why won’t it stop, and where does it come from?

Viral hypes can come out of nowhere

The answer, according to Watts: they come out of nowhere.

That’s partly what makes them so surprising and interesting to media: viral hits are (usually) not the result of some big brand spending a million dollars to make something go viral.

Not for lack of trying, because big brands do actually spend millions of dollars to make things go viral. But they don’t succeed. Whereas other stuff – completely random cat videos, toddler videos, dashcam recordings of unknown people suddenly get a life of their own.

…an initial shock can propagate throughout a very large system, even when the shock itself is small.

Duncan Watts

This is exactly what happened with the Ice Bucket Challenge: it came from a small corner of the internet, gained momentum, went viral, and then it just kept going, and going, and going.

Viral hypes can look spectacularly different, and yet they’re all the same

It’s not just cat videos or ice bucket challenges that go viral, says Watts. In fact, while Facebook certainly helps to cause and maintain certain viral hits, you don’t even need the internet to cause an information cascade.

In 1989, citizens of Leipzig took to the streets to protest communism on a Monday evening. They started out with a few thousand. A few Mondays later, there were tens of thousands of protesters. Then, hundreds of thousands. Next, other cities joined the marches. In the end, the Berlin Wall (and with it, the Eastern Bloc) came tumbling down.

The Leipzig marches started with a few thousand people. Eight weeks later, half a million people marched through the streets and the Berlin Wall fell

The Leipzig marches, like the recent demonstrations in Hong Kong, and the Arab Spring a few years ago, were not the result of careful planning. Nor were they advertised with huge budgets. They happened, they grew, and they grew more, until they were so huge that they toppled regimes which (until then) looked like it had its dissidents well under control.

Although they are little remembered now, the Leipzig parades probably qualify as a true turning point in history. Along with so many everyday revolutionaries before them, the Leipzig marchers demonstrated that cooperative unselfish behavior can emerge spontaneously among ordinary people, even when the potential costs—imprisonment, physical harm, and possibly death—are extraordinary.

Another example is recycling, says Watts. A few decades ago, it was an activity for fringe environmentalists. Today, not recycling is considered weird and even antisocial:

In less than a generation, much of the Western industrialized world altered its daily patterns of behavior in response to a distant environmental threat that previously had been perceived as important only to a handful of long-haired tree huggers.

More information cascades can be observed on the financial markets: from the famous tulip bubble that swept the Netherlands in the eightteenth century to the sub prime crisis in 2008 – “they are different manifestations of the same problem”, says Watts.

So, how can we cause a viral hype?

Because admit it, that’s what you want to know. It’s also what Watts set out to find out:

Did networks have weak points—structural Achilles’ heels—such that if they were hit in precisely the right way, a small shock would explode like an epidemic, each successive decision generating the conditions for the next? And if so, could one exploit that knowledge to enhance the likelihood of a cascade?

It turns out there is, but it’s harder than it looks. It has to do with how humans process information: people generally turn to other people to make up their minds.

The easiest way to make a decision is to look at what the other people in your network are doing. What’s the dress code for your company? It’s what your colleagues are wearing. So that’s what you wear.

The chances that you will participate in the Ice Bucket Challenge, then, are higher if all of your friends and colleagues are doing it.

Social contagion is a highly contingent process, the impact of a particular person’s opinion depending, possibly dramatically, on the other opinions solicited. A negative opinion of a potential job candidate, for example, might be the kiss of death if it comes on the back of prior negative remarks, or it may be discounted entirely if followed by a slew of positive reports.

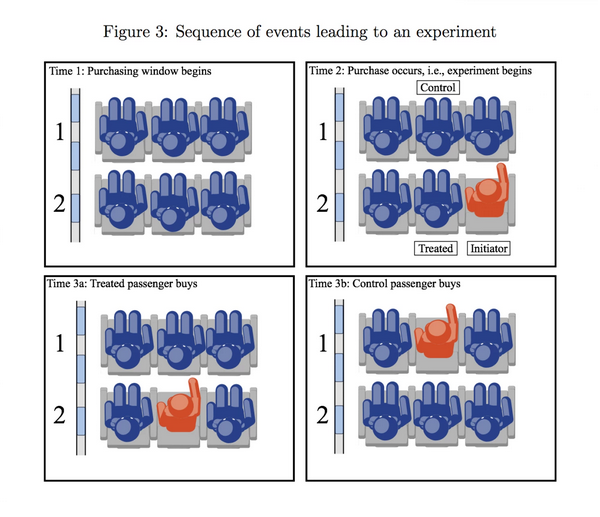

A social decision rule, therefore, looks something like Figure 8.2, where the probability of choosing outcome A increases at first very slowly with the fraction of neighbors choosing A, before jumping rapidly once a critical threshold has been exceeded.”

In human language: if only one of your friends is doing something weird, then the chances are low that you will join him. However, if all of your friends are doing it, chances are you will assume that it’s time you also start doing this – whether it’s crossfit, or wearing striped socks, or growing a hipster beard.

This was substantiated in a fun bit of research on people’s behavior during flights. Apparently, the chances of you ordering a movie on the entertainment system of the plane is a lot higher if someone else around you is ordering something. Or, as the Washington Post put it: “People around you control your mind.”

(source: http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/storyline/wp/2014/12/04/people-around…)

On average, people bought stuff 15 to 16 percent of the time. But if you saw someone next to you order something, your chances of buying something, too, jumped by 30 percent, or about four percentage points.

“That magnitude I really didn’t expect,” Gardete says. “It’s crazy, crazy.”

The fun thing is that there is a treshold for influence, says Watts. Below this treshold, not much is happening. Once a certain treshold is reached, your network just lights up like a Christmas tree.

Viral hits are rare

Even thought it seems like every week brings a new “viral hit”, it’s important to realise that these true viral phenomena are rare. Most efforts to create a viral hit fail miserably, despite the sometimes huge advertising budgets behind them.

These are the campaigns that gain some traction, but they never really take off, at least not in the way that the Ice Bucket Challenge did.

A network – whether it is the financial system, the power grid or the social graph is usually very stable, observes Watts. It has to be, because it is constantly exposed to external shocks, and it evolved to withstand most of them:

(…) one of the most intriguing features of the cascade problem was how most of the time the system is completely stable, even in the face of frequent external shocks.

But once in a while, networks are not robust, and an even insignificant initial shock can cause a cascade that overwhelms the entire system:

Once in a while, for reasons that are never obvious beforehand, one such shock gets blown out of all proportion in the form of a cascade. Cascades, therefore, will tend to be very rare (…). Once in a while, however—and this could mean one time in a hundred or one in a million—a random innovation will strike the vulnerable cluster, triggering a cascade.

‘Six Degrees’ explains this as follows: viral hypes can start from very humble, almost inconsequential beginnings. However, for a viral phenomenon to form a shock needs to hit a certain pocket of people in the network – a cluster of people who are able to “switch on” or “light up” the entire network.

This cluster has to have specific, and even contradictory characteristics. For one thing, it has to be both connected enough, but not too connected.

Imagine the first Ice Bucket video ever was sent by the originator of the Ice Bucket Challenge to a friend who has no other friends.

The video and the idea behind is catchy enough to pique interest, and it’s for a good cause, so our second friend doesn’t hesitate and pours a bucket of ice over his head. The originator of the Ice Bucket Challenge successfully managed to create virality: he “infected” a person with his idea. Unfortunately, because our friend doesn’t have any other friends, the bucket challenge is now dead, because it has nowhere left to go.

But on the other hand, if you hit a cluster of very well connected people, you need to be sure that enough people will join the fun.

Say you are launching a startup, and you hope to convince the startup community in San Francisco to start using your new cloud solution. You will release your new cloud solution on Hacker News, because that’s where your target group gathers. There’s nothing wrong with your plan – and it might even work – but the chances that you will create an immediate hit are small, because these startup founders have such huge networks, that your software might not reach enough early adopters fast enough to gain traction.

So here your viral hit was “denied” by the network because startup founders are too well connected.

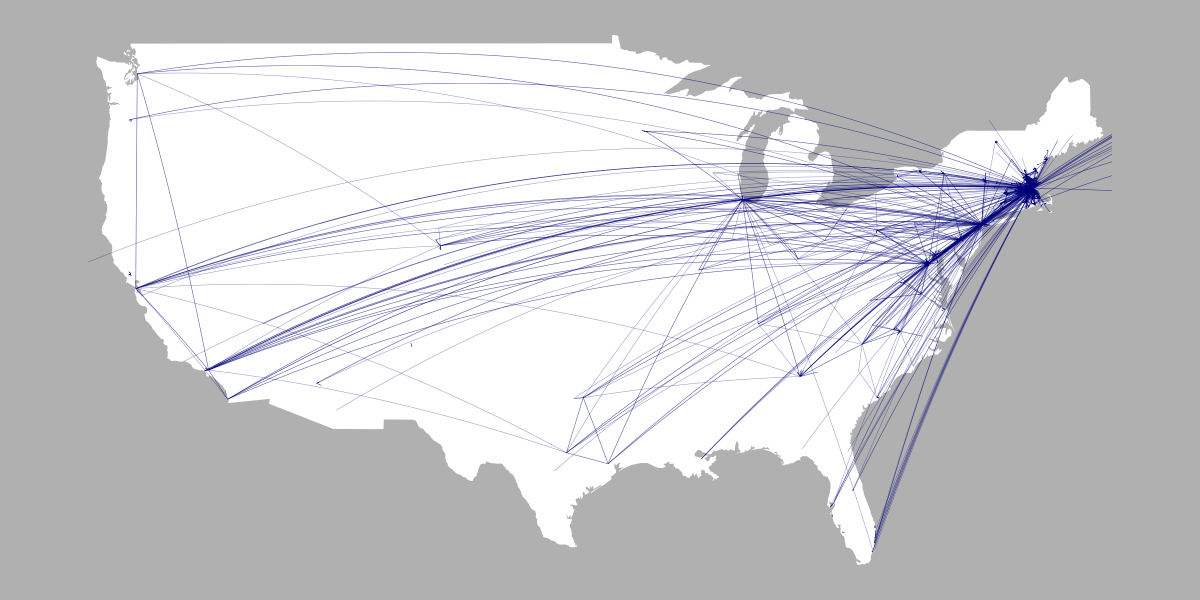

In order to create a real viral hit, you need to find an individual or a few individuals who are well connected (that’s the easy part), but who are also connected to the kind of people who are very likely to be influenced by these individuals (that’s the hard part).

Viral hits might be about pure luck, in the end

Watts’ conclusion is that it might be that the huge successes had less to do with intrinsic qualities of the phenomena, and more with the kind of cluster that they hit:

being simply well connected is less important than being connected to individuals who can be influenced easily. (…) So even if you can identify potential early adopters, unless you can also view the network, you won’t know whether or not they are all connected. (…)

It could just be that some innovations—Harry Potter, Razor Scooters, Blair Witch Project—hit just the right pocket of people, while most do not. And in general no one will know which one is which until all the action is over.

This is something that was hard to explain to a few journalists who called us to ask about the Ice Bucket Challenge. They wanted to know what it was about the Ice Bucket Challenge that made it so viral.

- Was it the fact that it was for a good cause? Partly.

- Was it the fact that it was fun? Partly.

- Was it the fact that it was more or less “transactionally viral” (I do something and by doing so I infect new people)? Partly.

But there are thousands of initiatives with the very same characteristics which fail.

In the end, the explanation for the Ice Bucket Challenge is not about the Ice Bucket Challenge. It is about the way people are connected today, and about the way people make decisions. As Watts says:

And so it is apparently with cultural fads, technological innovations, political revolutions, cascading crises, stock market crashes, and other manners of collective madness, mania, and mass action. The trick is to focus not on the stimulus itself but on the structure of the network that the stimulus hits. In this respect, there is still a great deal of work to be done.

Duncan Watts, Six Degrees

That’s not to say that Watts’ insights don’t hold useful information for PR professionals. Here’s what we incorporated in our PR work after reading Watts:

1. Map the network of the network

Map the network of your network of influencers. In other words, ask yourself: “Who influences my influencers?”

It was pretty clear that the Ice Bucket Challenge was getting so much media coverage because journalists saw their personal Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn-newsfeeds light up with Ice Buckets. This led them to write stories about it, which caused even more people to join the party. And so on. As Watts says, once this feedback loop starts, it is virtually unstoppable.

2. Flood the network

Flood the network as best you can, hoping to touch exactly the right pocket that will carry your message far further than you had hoped.

This is not the same as “spraying and praying” – sending e-mails to a huge number of people who are not connected to each other or your customer or yourself.

You are much better off trying to hit a well defined cluster of people that you have a chance of influencing, and who might be able to “switch on” their own network. The key here is mostly about timing, I think.

In today’s world, our network is no longer one dimensional. Most people are active on different networks (LinkedIn, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, YouTube, some vertical forums and media, Facebook groups,…). As we saw, people need a certain amount of their peers to “switch on” to pique their interest.

You need to understand very well where your influencers are active, who they are listening to – and then create a swift, well executed push across their entire network. The journalist, blogger or policy maker you are trying to reach has to see that enough people that he or she trusts and follows are taking up your message, on different platforms, at the same time.

3. Create velocity

In flooding, pay special attention to the timing: you want to light up the networks of your influencers all at once. You have to create velocity.

It’s better to have the entire network light up with a subject than to have it drip, drip, dripping into the network – while that might also be useful, it will make it harder or even impossible for a cascade to start.

The need for velocity is also the idea behind “Thunderclap”, which claims to help campaigns to boost their signal in the network (thereby increasing the chance to hit a percolating cluster): “By boosting the signal at the same time, Thunderclap helps a single person create action and change like never before.”

While Thunderclap is identifying the right problem, I’m not sure that it’s the right answer to the problem. I’m sure Thunderclap can help you increase your reach. But as we saw, you specifically need to reach and convert the people who will influence other people, and Thunderclap is unable to offer this assurance.

Creating velocity is hard, especially given the algorithms of Facebook and Linkedin. Facebook and LinkedIn posts will turn up hours or even days after you posted them, at unpredictable times.

On the other hand, LinkedIn and Facebook (and Huffington Post and Buzzfeed) were built by people who studied Watts’ book religiously – the algorithms in LinkedIn and Facebook are made to recognise this kind of “velocity” as we call it at FINN. When you manage to create enough velocity, algorithms will kick in, because they recognise the pattern – and the social networks will create your information cascade for you. (Sweet!)

This is how we explain it to clients:

What PR looks like from the outside – and what it really is on the inside from FINN

4. Don’t think you will replicate the Ice Bucket Challenge any day soon

Because:

It could just be that some innovations—Harry Potter, Razor Scooters, Blair Witch Project—hit just the right vulnerable cluster, while most do not. And in general no one will know which one is which until all the action is over.

Duncan Watts