For the third year in a row, FINN analysed how 50 of the largest Belgian companies reported on their carbon emissions. The conclusion? After slight progress last year (probably slow because Covid drew attention away to other matters), this year’s results show impressive improvement, even among the ‘worst in class’. The times, they are a-changing – for good now.

Three years of data show that companies increasingly acknowledge the importance of their non-financial reporting – often under pressure from different stakeholders, or to be more attractive to talent. But apart from the carrot, there’s also the stick. By January 2024, some of the largest and listed companies in Europe will have to submit their first report aligning with the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) (more details at the end of this blog).

Most companies are clearly evolving towards this deadline. What are the most interesting developments? We’re listing them below, before passing on to a list of insights to keep in mind when drafting your sustainability communication.

#1: Progress across the board, from top to bottom

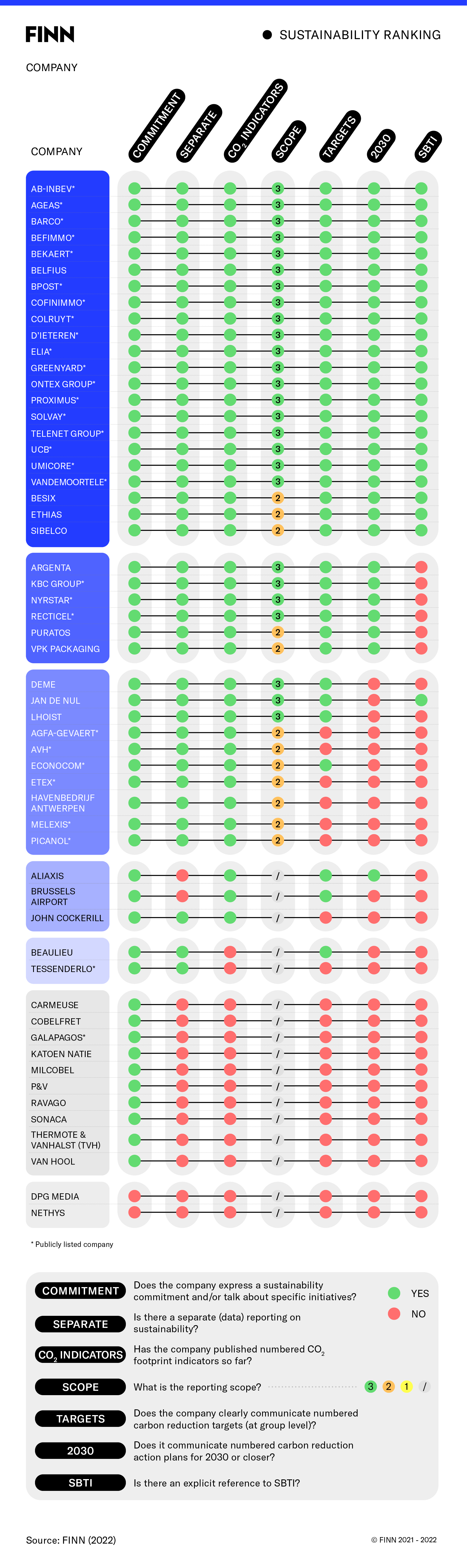

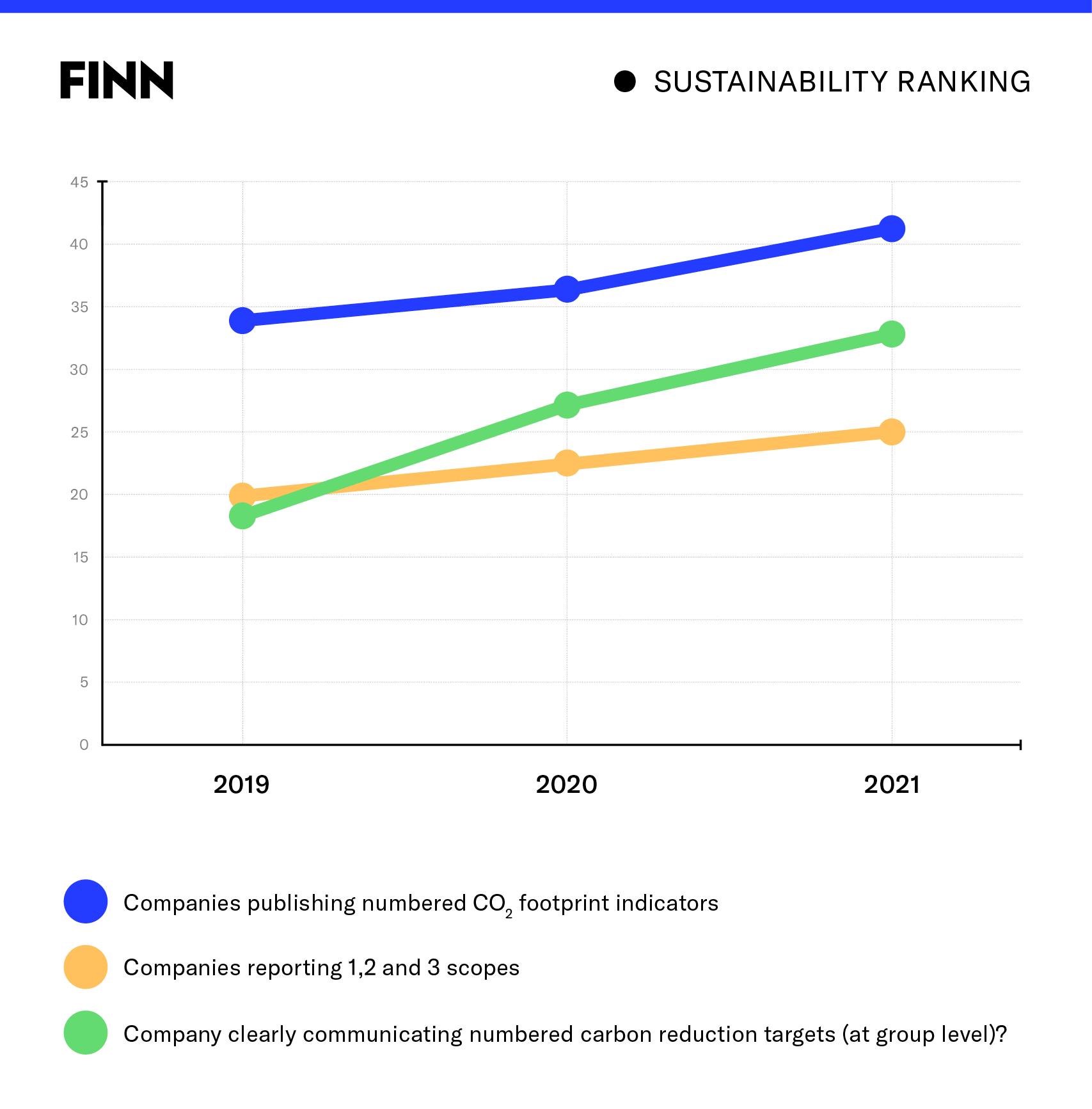

The ‘best in class’ group gets bigger and bigger – from 17 last year to 22 this year. But also the runners-up perform better each year, making the group of companies that are able to say ‘yes’ to the crucial questions larger each year (see visual). The reverse happens at the bottom of the list, where the group of less performant companies is shrinking. Even those that are not very precise in their targets, have started talking about sustainability commitments.

2021 showed – more than last year – a few impressive climbers. Sibelco moved up from tier 8 to tier 1, Sonaca initiated more professional sustainability reporting, Cockerill can’t show specific results yet, but showed real progress by launching a Sustainable Committee that reports directly to the Board, and Besix impressed with a very detailed action plan.

#2: Shorter horizons, more precise measurements

Almost two-thirds of companies communicate numbered carbon reduction targets (an increase of 32% compared to last year). Half the companies share numbered carbon reduction action plans for 2030 or closer.

This clearly shows that the time of vague plans and distant horizons is increasingly behind us. More and more companies are moving beyond the ‘yearly ladder’ calculations (how much better will we do next year compared to this year) and setting mid-term plans instead (where do we want to be in 2025 or in 2030?)

The annual reports show increasing precision when it comes to measuring results. A few years back, companies still boasted about initiatives like the installation of solar panels. Now, an increasing number of them share baseline measurements.

For the first time, we see SBTi (Science Based Targets initiative*) as a standard break through: among the ‘best in class’, while 22 out of 28 companies refer explicitly to SBTi in their yearly sustainability reports.

Challenge 1: Will we see ‘CO2 warnings’ in the future, just as we have ‘profit warnings’?

With lots of companies publishing hard and very specific deadlines (more and more of them refer to the moment they will become ‘Net Zero’**), one wonders: Will all of those companies manage to get the results they promise? The more that companies publish CO2 numbers and targets, the more they will be exposed to expectations. It seems almost inevitable that some of them will have to send out rectifications to their CO2 forecast.

Challenge 2: Is there too much to report on?

When it comes to non-financial reporting, a lot of ESG aspects are covered, from environmental impact, over societal responsibilities, to governance.

You can feel that organisations are quite stretched at this point: There are data on gender balance, stories about initiatives for the community, explanations about corporate governance,…

It made The Economist wonder this summer whether ESG isn’t deeply flawed, because it risks setting conflicting goals and distracts ‘from the vital task of of tackling climate change.’ Hence the suggestion it makes to focus solely on the E, and more specifically on 1 specific aspect: emissions. We tend to agree.

Is ESG deeply flawed because it distracts ‘from the vital task of tackling climate change’?

The Economist, 2022

In order not to get lost in the multitude of data and stories, we would advise companies to think thoroughly about their CO2 story:

- Just as companies build “equity stories” when preparing an IPO or a merger/acquisition, they are now collecting data, setting objectives and putting action plans in traction – all constitutive elements of a “CO2 story”. Reflect on the elements you have, and develop a storyline that brings together all those elements in a consistent, engaging way.

- What we noticed when going through the reports, is that progress needs to be made on the how. It’s ‘easy’ to set targets, but how will you reach them? That is still not very clear for some among the biggest Belgian companies. Be transparent about your plans and how you will manage the results you obtain.

Challenge 3: Who said ‘standard’?

Investors have been pleading for years for global standards in sustainability reporting that make it easier for them to compare assets.

As Sandy Boss from BlackRock once put it, ‘Greenwashing will only disappear when companies start reporting uniformly.’

Some of the companies we reviewed indicate that several of their portfolio companies use different measurements, so at times, there isn’t even a common standard within one company.

Tessenderlo Group uses the lack of a global standard as an argument for not measuring its carbon footprint. ‘Carbon footprints can only be compared on a comparable basis,’ it says in its CSR report 2021.

‘Neither our emissions nor our carbon footprint are currently reported. As there are various different approaches for calculating the carbon footprint, which result in rather different outcomes (e.g. mass allocation, economic allocation, etc.), we would like to see further progress regarding a regulated standardization in this context.’

Tessenderlo Group

The lack of a common standard indeed makes it hard to read and compare reports, and truly understand what companies are reporting on (scope, science based, targets by when,…).

We would give companies the following advice:

- Add an executive summary, explicitly explaining what you measure and what not

- Be very explicit on what you do and don’t

- Adopt the ‘comply or explain’ principle (which already exists for governance)

- Explain the framework you are working within (be it SBTi, GHG Protocol,…)

- Checklists help readability for stakeholders (don’t put everything in text)

Conclusions

The deadline for compliance with the CSR Directive is coming closer, and companies are getting into gear. After a rather slow progress in the Covid year 2020, 2021 has been a break-through year, showing significant progress in reporting on CO2 emissions.

Apart from compliance reasons, companies have understood that communicating about sustainability has a huge up-side when engaging with stakeholders, not in the least with (future) talent. The professionalism of the yearly sustainability reports is increasing year after year.

Methodology

We included companies with a Belgian capital base whose size is measured on the basis of their 2019 turnover. We removed financial holding companies and trading companies from the sample.

We based our analysis on the latest annual reports published before 31 August 2022 (both financial and CSR/sustainability), and on the corporate websites of these companies.

In the first 2 years, our analysis was on based on 5 questions:

- Does the company express a commitment to sustainable development and/or present concrete initiatives?

- Does the company engage in specific sustainability reporting, including quantitative data?

- Has the company published its carbon footprint, with supporting figures?

- What is the scope (1, 2, 3)?

- Does the company communicate clear and quantified CO2 reduction targets (at group level)?

Starting from 2021, we added two more questions:

- Does the company communicate numbered carbon reduction action plans for 2030 or closer?

- Is there an explicit reference to SBTi?

The purpose of our research is not to judge decarbonization ambitions, their alignment with the objectives of the Paris Agreements, the choice of “metrics” or the credibility of the plans undertaken by companies, but rather the way they communicate on this subject.

Context : a tightening legal framework

A new decisive step towards the approval of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) was taken at the beginning of this summer, with the adoption of a common position by the Council of the European Union and the European Parliament. The CSRD aims to create a system that will define sustainability standards with uniform, proportionate, understandable, verifiable and comparable information.

The directive will gradually apply to all EU companies, starting with listed and large companies. To comply with CSRD, these entities (matching at least 2 of the 3 following criteria: a balance sheet total of EUR 20 million, a net turnover of EUR 40 million, or 250 employees or more) will have to submit their first report aligning with the CSRD on 1 January 2024, for the 2023 financial year. Small and medium enterprises will, for their part, have to start reporting to a separate, proportionate reporting standard for the financial year 2026.

The last few months have seen new rules resulting from the European MiFID and IDD directives come into force. These require banks, insurance companies and fund managers to communicate more clearly on the sustainability of their financial products, and therefore of the companies in which they invest.

As an effect of the increasingly demanding regulatory framework and market pressures, the production and communication of data relating to a company’s sustainability has definitely moved from being a “nice to have” to being “essential”. Because many details in the European legislative arsenal are not yet finalised, including the taxonomy classifying the different business sectors according to their sustainability, many actors claim that they do not have the tools to do proper reporting

However, while waiting for the final approval of CSRD, the European Commission has entrusted the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) to work on a first set of CO2 and other sustainability reporting standards, to be adopted by the EU Commission by the end of October this year. EU Member States will then have to adopt the EU Directive into national law by the end of 2023.

In its consultation phase, the EFRAG already unveiled a first overview of the expected CO2 reporting requirements. These include the establishment of absolute CO2 reduction targets:

- encompassing scope 1, 2 and 3 (see our previous study for details on that),

- from 2025 on a 5-year rolling period

- possibly science-based

*The Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) is a collaboration between the CDP (was Carbon Disclosure Project), the United Nations Global Compact, World Resources Institute (WRI) and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).[1] Since 2015 more than 1,000 companies have joined the initiative to set a science-based climate target.

**Individual Neutrality and Net Zero

Carbon neutrality is the balance to be achieved between greenhouse gas emissions and their removal from the atmosphere by humans. Some companies claim to be neutral through offsetting projects such as reforestation, or capture and landfill.

But the concept of neutrality at the level of a single company is now being rigorously debated. A world in which everyone continues to increase their emissions but achieves individual neutrality every year through the massive use of offsets or extractions would be synonymous with permanent imbalance.

Hence the emergence of the “Net Zero” initiative, which sets a common frame of reference for more effective action. A company contributes to global carbon neutrality through plans to reduce its direct and indirect emissions as much as possible as well as by reducing the emissions of others (marketing and financing of low-carbon solutions and projects).

For the absolutely incompressible part of its emissions, it finally increases its carbon sinks at home and in its value chain. For each stage, tools and standards exist (Bilan Carbone®, SBTI, GHG Protocol, etc.).