Creating a true corporate communication strategy is still a challenge. Even in large companies, we regularly see communication departments without a documented corporate communication strategy.

That is surprising because CEOs invariably say that they expect their chief communications and public affairs officers to be true “strategic” partners.

As explained in a survey among CEOs by Egon Zehnder:

CEOs expect their chief communication officers to bring more than just a high level of specialist expertise to the table – they also expect management and strategic competencies, above all. Almost without exception the CEOs questioned say that they want their CCO to be a kind of sparring partner.

If strategic competencies are so important for CEOs, why don’t their strategic partners have a strategy?

In our work, we see that the problem stems from the corporate communication strategy process – or rather the lack of a good process.

Tell me if this sounds familiar: you are asked to come up with a corporate communication strategy. You make the rounds of several departments and management layers to get their input.

You schedule meetings with top management, HR and some business unit leaders. They all deliver you the shopping list of their “strategic” priorities. Next, they ask you to fit all this information into a strategy, but what they mean is a calendar which neatly includes all their priorities.

By the time you’re finished, you have a full workload for the year, but not a strategy. You created a calendar.

Here’s how you can build a true corporate communication strategy, by making a few smart changes in your process.

What strategy is – and what it isn’t

First, it helps to have a clear vision of what a strategy should do.

According to Richard Rumelt, the author of ‘Good Strategy, Bad Strategy and why it matters’, a good strategy “honestly acknowledges the challenges being faced and provides an approach to overcoming them.”

A good strategy, says Rumelt, consists of three parts.

“Where are we today?” (the diagnosis)

It all starts with a cold, hard look at yourself. Where are you today? What goes well? What goes wrong? What opportunities are you missing?

The most important work in this stage is simplifying the many obstacles and opportunities into a consistent story about where you are.

You don’t want a simple list of challenges. You want a story that is easy to understand and at the same time covers the underlying complexities. Creating a strategy is always a storytelling challenge.

Says Rumelt:

A diagnosis (…) defines or explains the nature of the challenge. A good diagnosis simplifies the often overwhelming complexity of reality by identifying certain aspects of the situation as critical.

“How can we get to where we want to be?” (approach)

Second, Rumelt advises defining an approach to overcome your challenges (and reap the benefits of any opportunities):

an overall approach chosen to cope with or overcome the obstacles identified in the diagnosis.

“What should we do to get there?” (actions)

Finally, a strategy includes the actions you will take to address your challenge.

From this simple description of strategy, we immediately see the difference with the “calendar” approach described above. It’s fine to ask for input from different departments, but the risk is that they will scatter the attention of the corporate communication department instead of focusing on it.

A scattershot approach to challenges is the biggest enemy of strategy, says Rumelt:

Most complex organizations spread rather than concentrate resources, acting to placate and pay off internal and external interests. (…) Thus, we are surprised when a complex organization, such as Apple or the U.S. Army, actually focuses its actions. Not because of secrecy, but because good strategy itself is unexpected. (…)

And then he adds this gem:

Strategy is at least as much about what an organization does not do as it is about what it does.

The place of corporate communication strategy

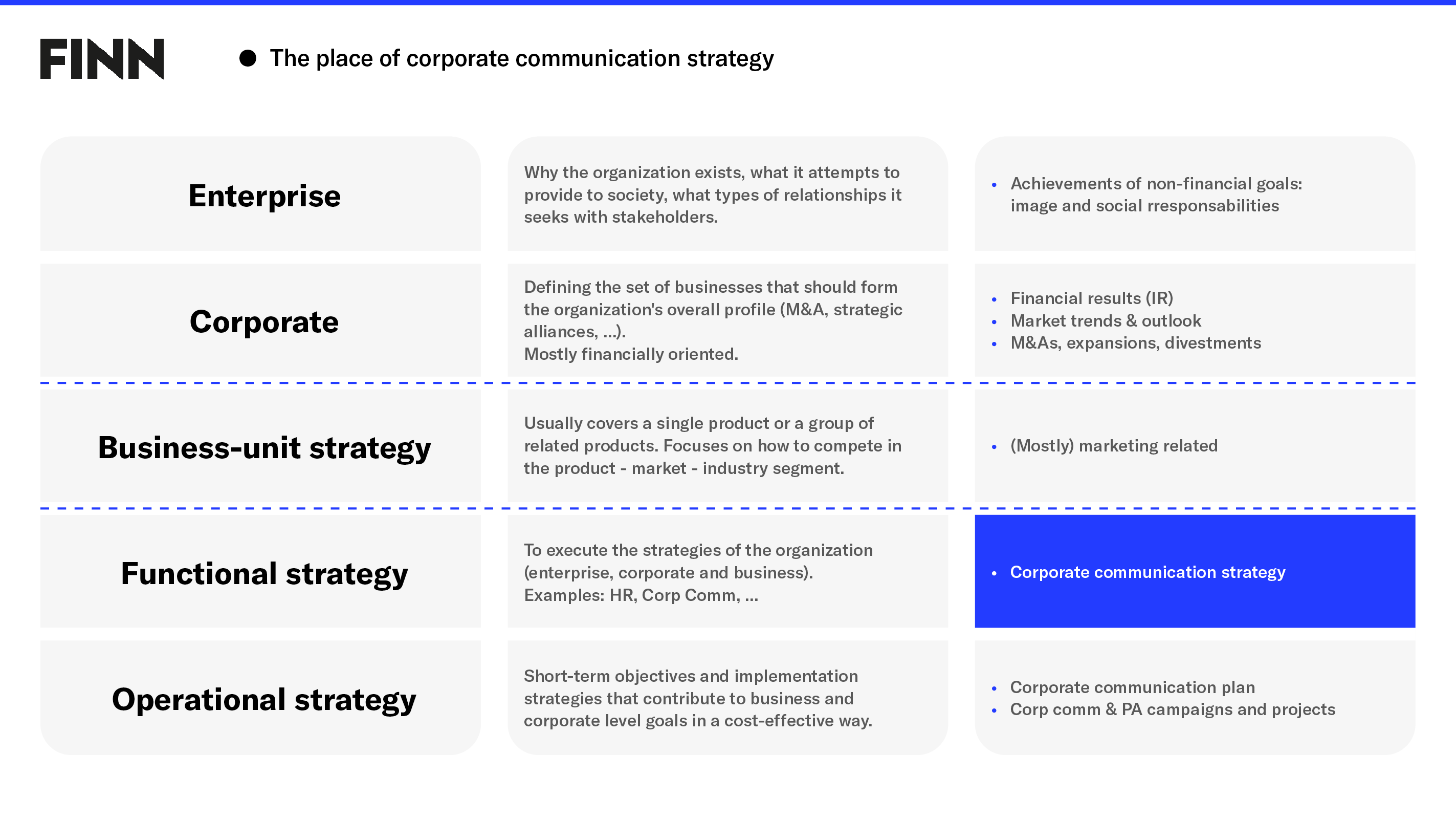

It also helps to have a clear grasp of where corporate communication strategy ranks in the order of things. Business literature distinguishes different types of business strategies:

- Enterprise strategy: defines what the organization wants to be on a societal level – what do we want to achieve for stakeholders? It’s the most aspirational level of the strategy, also known as Simon Sinek’s “why” or the purpose

- Corporate strategy: defines in what disciplines and segments we want to compete – where do we want to play? (A mostly financial level, dealing with acquisitions, divestments,…)

- Business strategy: what kind of business units do we have and how do they compete in the marketplace (a level that is mostly about marketing)

- Functional strategy: how can the business functions help realise the enterprise, corporate and business strategies? This is the level where HR, corporate communication, finance, legal,… come into play

- Operational strategy: how will we do all of the above? This is the level of planning and execution

The answer to our question is that corporate communication strategy should make it possible to achieve enterprise, corporate and business strategies.

At the same time, the role of corporate communication is to give input to the enterprise, corporate and business levels about what is going on in the outside world and how that affects the organization.

If the corporate communication department can achieve those things – if it can help support the enterprise and business strategy through communication and it can offer insights to refine those strategies – then it will be well on its way to becoming the “sparring partner” that the CEO is looking for.

Corporate communication strategy: a theoretical framework

Now the question is, how can we build such a corporate communication strategy that plugs into and supports the larger business strategy?

Joep Cornelissen offers a good framework, building on Mary Jo Hatch and Majken Schultz’s model for corporate brands.

Summarized, this is how Hatch and Schultz see the corporate communication strategy:

Everything starts with the vision, as formulated by the board and the C-level of the organization. It’s the purpose (the why) but also the how and the what of the strategy.

Unfortunately, this vision in itself will never define your corporate brand.

Why?

Because there are always “gaps” between what you want to achieve (your vision), how your team interprets and executes it (the culture) and how your stakeholders experience it (your image).

Example: Imagine a large bank.

The CEO and board might agree that they want to shift the bank’s strategy towards sustainability. But your local branch manager might still sell you funds that score very poorly on ESG metrics – and tell you that he doesn’t believe in “those woke funds from HQ”. What you experience is

- a vision-culture gap (the branch manager not believing in “woke funds”, and the vision established by the top management),

- a culture-image gap (the bank’s customer experiences confusion because there is a gap between what the employees of the bank deliver and what the bank states in its vision on sustainability)

- an image-vision gap (the customer and external stakeholders no longer trust the bank to deliver on sustainability promises)

Hatch-Schultz is a great mental model for understanding what a strategy needs to address.

But it’s not a process to build the corporate communication strategy. Which is why we need a more practical approach.

A corporate communication strategy process in seven steps

1. Preparing the corporate communication strategy: input and research

It’s not the role of the corporate communication department to single-handedly decide on the corporate communication strategy. You will co-create the strategy with C-level, board-level, and possibly other internal stakeholders (business unit directors).

Before you can do this, you need to help them by doing some research.

First of all, check with your management whether the vision of the organization is still up to date.

We use “vision” in the largest possible sense, including the “why” (purpose), the “what” (positioning, corporate strategy) and the “how” (values, culture, identity).

If small nuances have changed, update the vision immediately. If you need a big overhaul of the purpose, then this might become part of your strategy for the next year.

Next, check the existing culture and image.

Useful tools to understand where your corporate brand includes:

- Reputation tracker

- Media clippings (eg: a media reputation index)

- Brand tracker

- Issues & Stakeholder mapping

- Crises that the organization went through recently

- Social media interactions and reviews

- Regulatory reports

- Complaints, litigation

- Employee Surveys on engagement, culture, …

The output of this first phase is a document or a presentation. It allows your colleagues to have all the relevant information on the current situation at the company – the good, the bad and the ugly. This is necessary before you can go to the next part of the corporate communication strategy process: the workshop.

Ask your colleagues to read the document, or take them through the presentation. This way, the decision-makers have the same information as they go into the workshop.

2. Workshop

In this workshop, members of management (Chief Executive Officer, Chief Human Resources Officer and other relevant members of management) work with members of the corporate communication team to give input on the strategy.

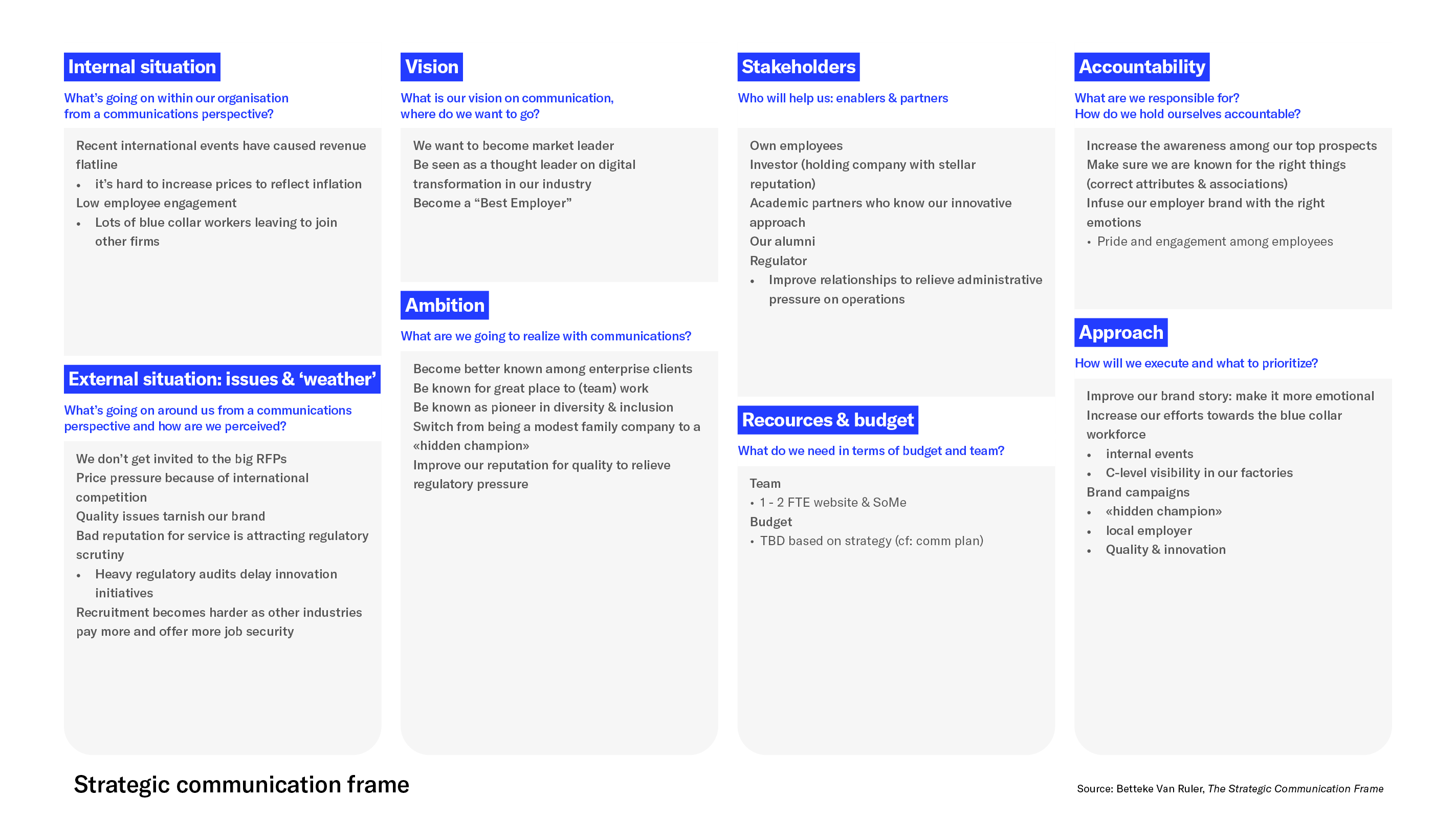

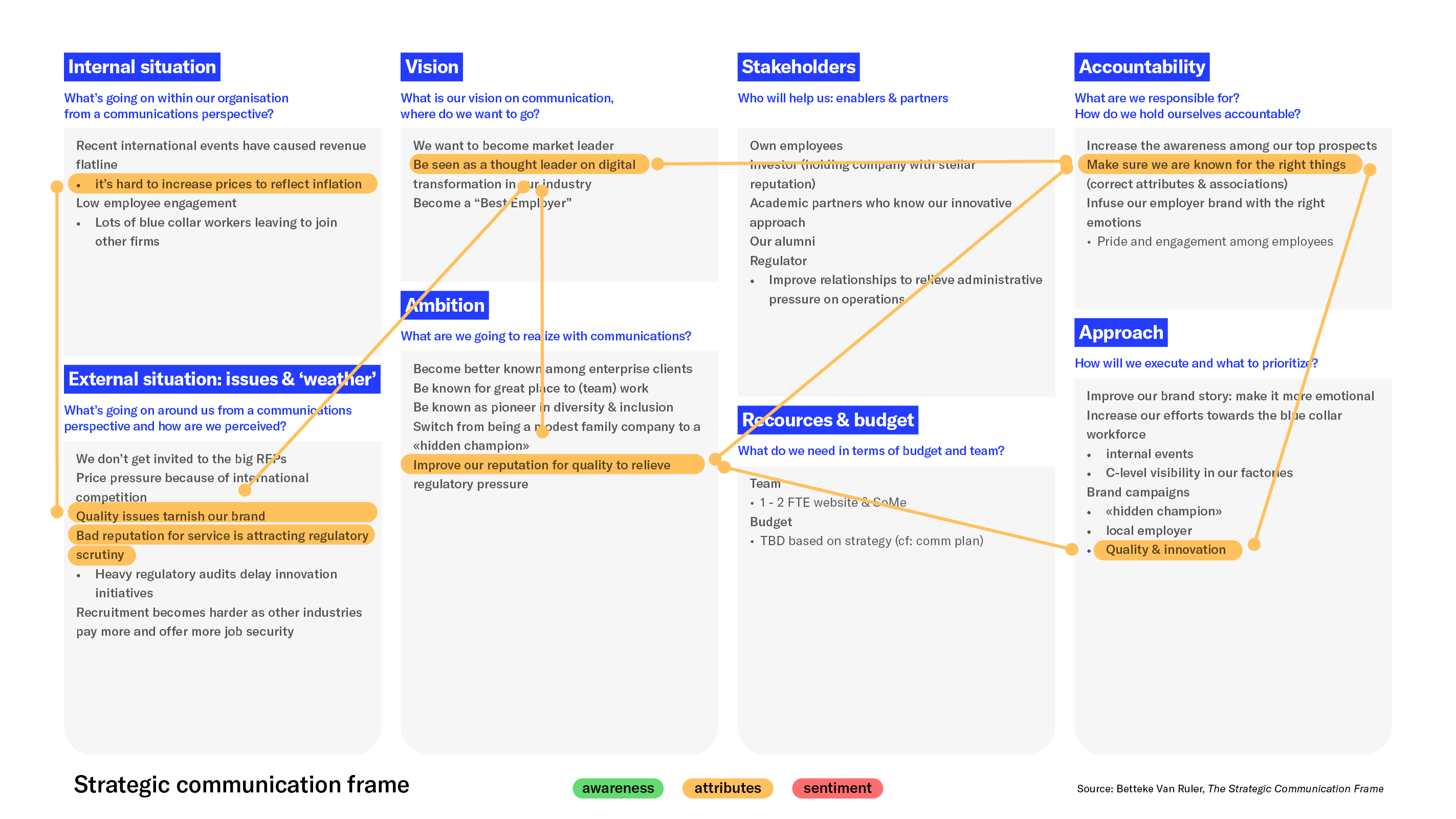

We found that the best way to organize this workshop is to use the ‘strategic communication frame’ as developed by Betteke van Ruler and Frank Körver.

The communication frame is a variation on the ‘Business Model Canvas’.

The left side half of the canvas describes where you are & want to go:

- Where you are today (“internal situation”, “external situation”)

- What you want to achieve (“vision” split up into “vision” and “ambition”)

The right-hand side of the canvas focuses on how you will get where you want to be:

- Who can help you

- Resources and budget you need

- What your colleagues can expect from you (“accountability”)

- What steps, actions and tactics you will use to get there (“approach”)

In most workshops, we make an additional distinction between what the company wants to achieve and what the communication department wants to (or can) achieve.

Stuff that is too far outside the purview of communication or marketing has no place in the frame.

Use common sense to avoid a frame that becomes too crowded or detailed. Remember, a strategy is a “simplified story” of the complexity of the real world. During the workshop, you can already aggregate some things on a higher level, or cluster them. This will help you write your memo in the next step of the process.

Tips for filling in the canvas:

- You can use an online whiteboard like Plectica or Miro to fill it in, or you can use post-its on a wall (or both)

- Make sure you have a dedicated note-taker (or even two), whose job it is to make exhaustive notes including quotes (you will regret lost information when writing the memo)

- Don’t worry too much about the right-hand side of the frame yet (resources, KPIs, approach) – that will come later. Focus mostly on where you are today, what feels important and where you want to go.

The workshop will result in two documents:

- A rough, filled-in version of the strategic communication frame

- A strategic memo based on the notes

3. The strategic memo: the basis for the corporate communication strategy

The memo is the basis for your strategy. It is the most important document that you will create in this process.

It follows the structure of the communication frame, but it is much, much more detailed than the post-its on the wall or the short sentences that you have on your online whiteboard.

What’s important about this document:

The memo is not a “meeting notes” document. The structure is not chronological but follows the framework. If you put some things in the wrong frame box during the workshop, put them in the correct chapter now.

It’s detailed. Imagine a new CEO starting in a few months. You want a single, comprehensive memo of about 6 to 10 pages that brings them fully up to speed on every aspect that is relevant to the communication strategy. If they read the memo, they should understand why your strategy is what it is and what the underlying business challenges are that your communication programme is helping to solve.

The inputs can range from regulatory issues to employee engagement issues, to strategic initiatives on new products, to investment and divestment plans that will impact the brand.

The memo should already label issues and opportunities in communication or marketing terms.

So input like this:

CEO: We’re seeing huge pressure on pricing from Chinese manufacturers. They just copy our stuff at lower quality and flood the market. That makes it harder for us to raise our prices to match inflation. We just can’t raise our prices, we don’t have enough demand. You know, we’ve had those recalls, clients just don’t accept it when we raise prices – and we don’t get a lot of interesting RFPs right now.

Becomes something like:

Pricing power: price pressure caused by overseas competition erodes margins.

Brand attributes: quality issues and recalls have tarnished the brand.

Awareness and brand preference: we don’t get invited to interesting RFPs.

Remember that we said to take detailed notes? Without extremely detailed notes, you will not be able to write a comprehensive memo.

To keep your readers focused, don’t hesitate to use juicy quotes. Painful areas, compelling visions, recognisable stories or insightful interventions about the real issues will make your strategic document a lively snapshot of where you are with your organisation.

Put these inputs in descending order of importance for every part of the frame. In the above example, brand awareness must probably be tackled before the brand attributes, so put it first in your memo. What good is having the right brand attributes if no one knows you?

After you complete the memo, have it validated by all the participants of the workshop.

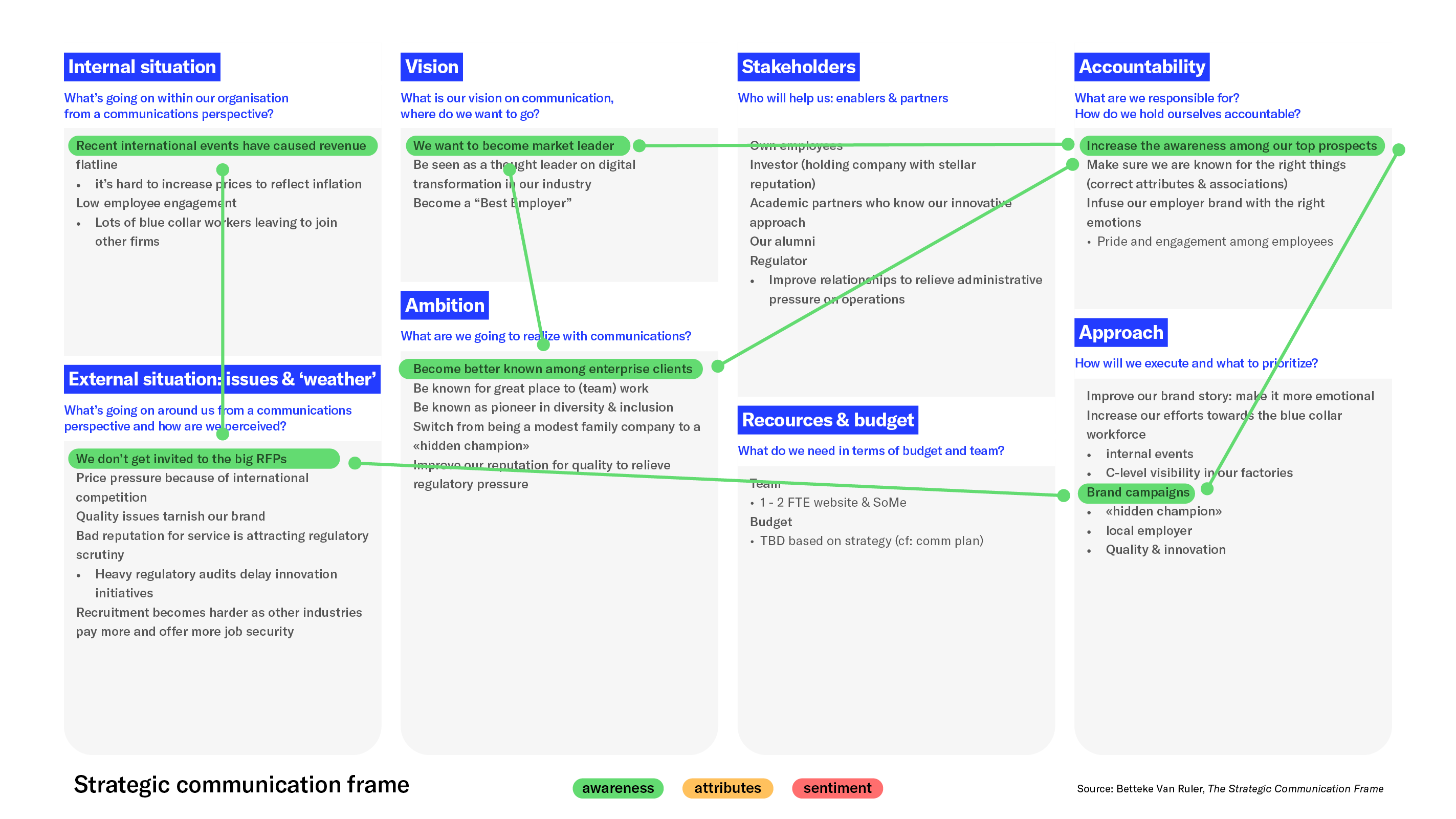

4. The communication strategy frame

Now that you have the validated memo, everyone inside your company agrees on what is going on in the world and the company, where you want to go and how you will tackle your challenges. Now you can go back to the frame.

You can now update the frame based on your memo:

- Correct any mistakes that you made, eg: if you put input in the wrong box, move it to the correct box

- Put the inputs in the correct order – the most important things come first

- Write down for yourself which key issues/patterns you start seeing and label them. Fi: “awareness”, “attributes”,… Mostly 3/4 of big issues emerge.

That will look a little like this:

As you can see, we haven’t bothered too much with KPIs, resources and budget yet. That’s for the next phase.

Now, use colour coding to connect inputs. If you labeled your issues correctly, patterns will become immediately clear.

Like in the example below, we highlight everything connected to “awareness” (do people know we exist). We added the 3 key issues and labelled them (bottom of the slide).

In the next one, we highlighted everything related to “brand attributes” (do people who know us, know us for the right reasons):

5. The corporate communication strategy goals

At this point, strategic priorities should become crystal clear. In the above example the priorities are:

- “People don’t know us” (awareness)

- “People know us for the wrong reasons” (brand attributes)

- “Employees and recruits lack emotional connection to the company” (sentiment)

- “Customers do not prefer us as a supplier” (preference, brand equity)

You should now be in a position to say where you will focus your efforts, and these efforts will be connected to the business strategy.

- Increase awareness

- Emphasise the right brand attributes

- Improve the sentiment around the brand towards internal and external stakeholders

In a sense, by now the hard work is done. You know what you want to achieve, and it’s closely connected to where the company wants to go.

This is where the communication department takes over to dive into the strategic approach: what will you do, how much of it you can do, how will you do it and how will you measure it.

The next steps in the process are where your creativity and knowledge will make a difference for the company.

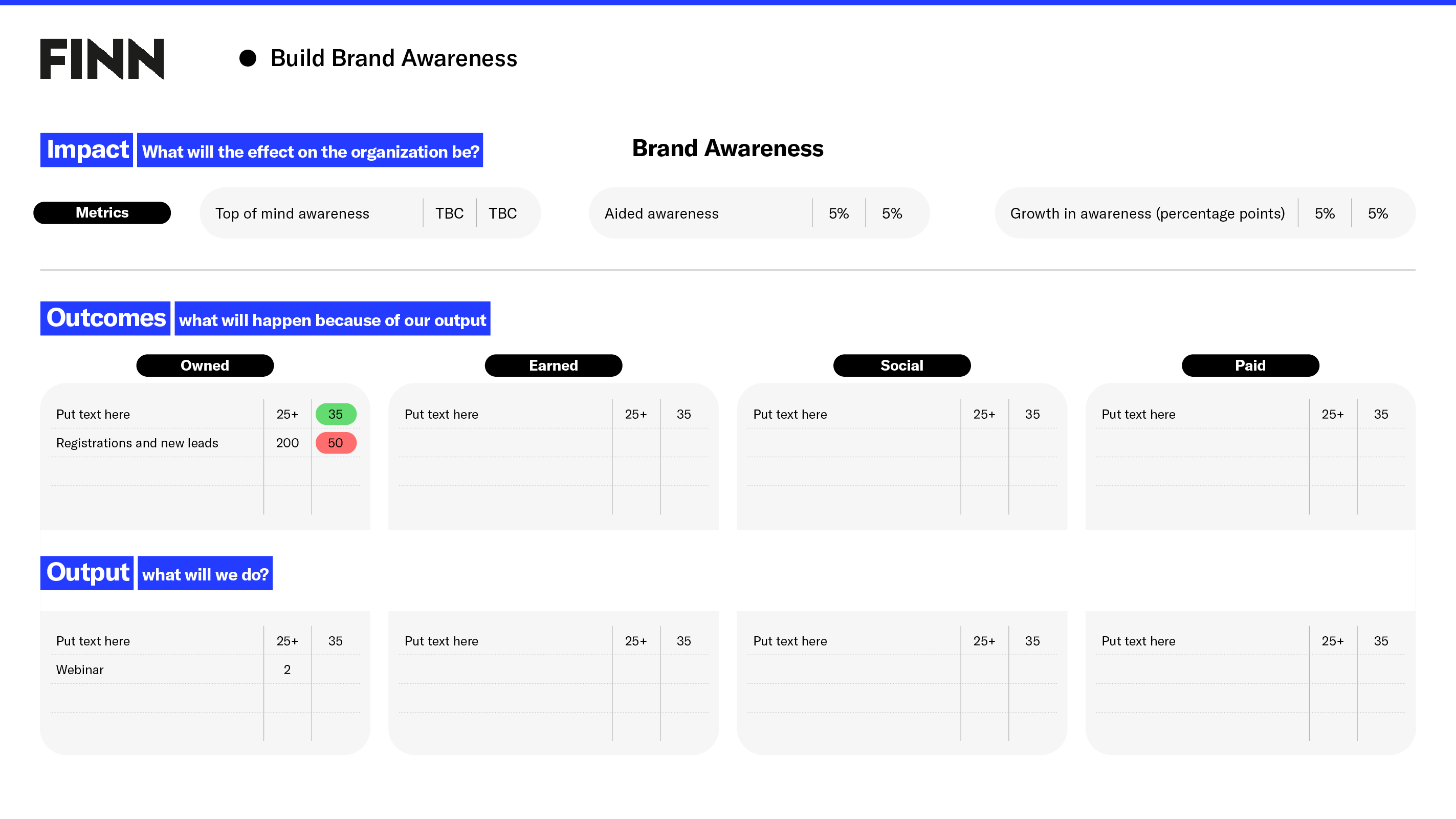

6. Corporate communication strategy: the “five hows” of KPI setting

This brings us to the next phase: setting those KPIs (in the frame: “accountability”)

For instance, if you aim to “increase awareness”

- by how much?

- do you even know where brand awareness is today?

- how do you think you can achieve that?

- using which tactics (PR? advertising?)

- using which channels? (LinkedIn, TikTok?)

- how much output is needed?

- what will that cost?

- who will support you in your efforts?

- how will you measure progress during the year?

- do you have a baseline metric to compare? do you need one?

You might have heard of the “5 whys” that are used to find the root cause of a problem. In the case of KPIs, replace this with “5 hows“:

- How can I raise awareness?

- By reaching more people

- How can I reach more people?

- By communicating more

- How can I communicate more?

- Increasing the number of communication campaigns

- Increasing the number of channels

- How can we know which channels we need to use?

- By measuring them for things like reach

- How can we measure them?

- Through dashboards, surveys, brand trackers

You will not have one KPI, but a pyramid of KPIs and metrics that should all help to achieve your goal:

As a rule of thumb, make sure you define KPIs on at least three levels:

- Output: what will we implement? which actions will we take?

- Outcomes: what should be the effect of these actions? How will the audience respond? Think of things like reach, media clippings,…

- Impact: what will be the impact on the organisational or business KPIs (eg awareness)

You get the idea. You will probably not manage to stuff all these detailed KPIs into the communication frame. That’s not a problem. The framework has served its purpose. The nitty gritty details of KPIs don’t need to be in it.

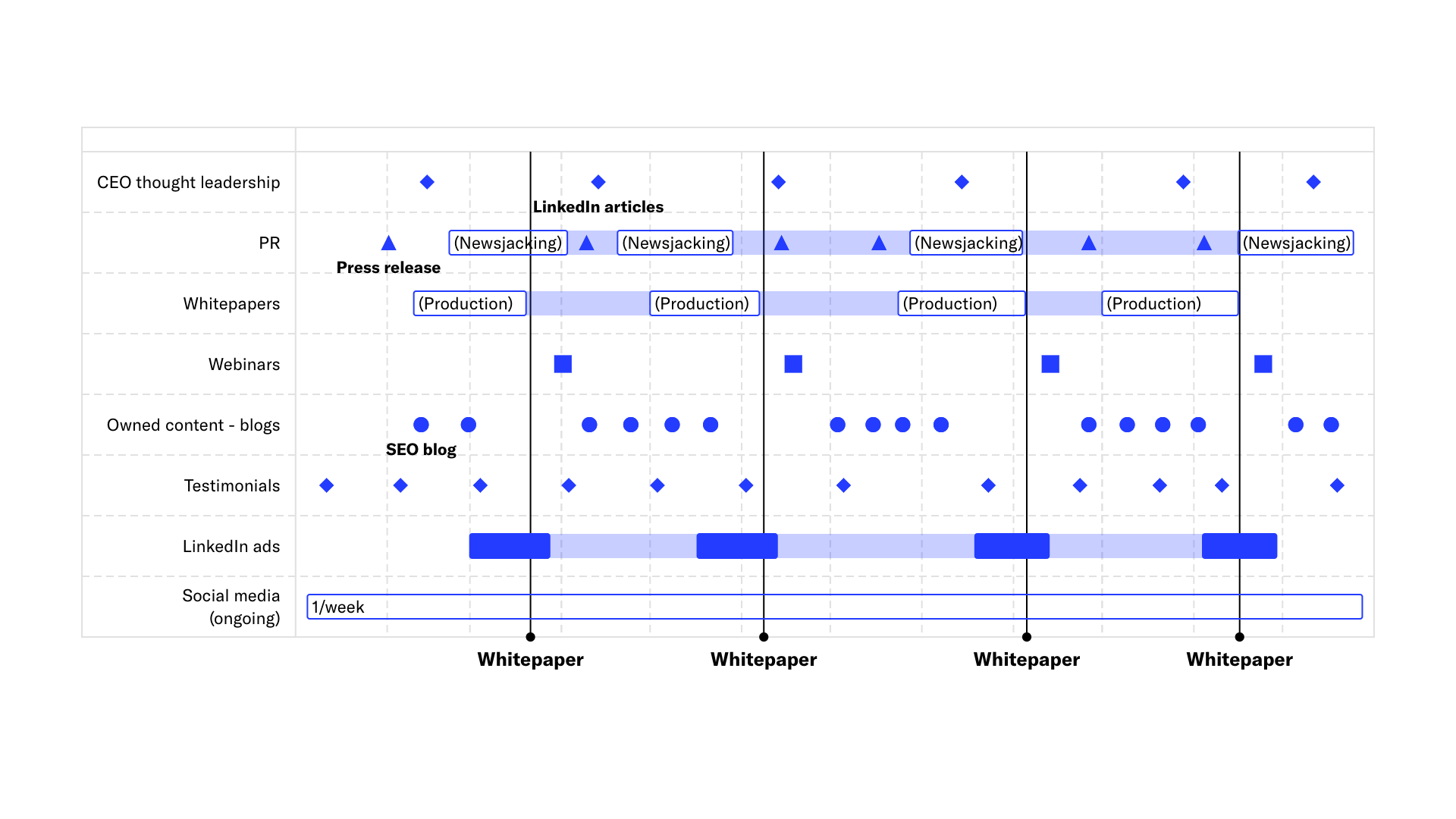

7. The communication plan

Finally, now that you have your KPIs, you need to put all of your planned output into a communication plan. This is a high-level plan for the campaigns and actions that you will run in the next year (or 2 years if you prefer).

That will look a bit like this:

Read more on how to create a communication plan

Now, you can bundle the strategic communication frame, the more detailed KPIs and the communication plan into one presentation and get sign-off on it from your management.

If you enjoyed this guide for corporate communication strategy…

If you enjoyed this blog post, please consider sharing it with your network or linking back to it. Thank you in advance!

Sources & further reading on corporate communication strategy:

- Egon Zehnder, “Communication from the CEO’s perspective – an underestimated challenge?”

- Richard Rumelt, “Good Strategy, Bad Strategy and Why it Matters”

- Joep Cornelissen, “Corporate Communication: A Guide to Theory and Practice”, 5th Edition

- Mary Jo Hatch and Majken Schultz, “Are the Strategic Stars Aligned for Your Corporate Brand?”, Harvard Business Review, 2001/02

- Benita Steyn, (2000) “Model for developing corporate communication strategy”, Communicare, 19(2)

- Benita Steyn, (2004) “From strategy to corporate communication strategy: A conceptualisation”, Journal of Communication Management, Vol. 8 Issue: 2, pp.168-183

- Betteke Van Ruler, Frank Körver, “The Communication Strategy Handbook: Toolkit for Creating a Winning Strategy”, Peter Lang, 2019, 174 pages