On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. addressed a crowd of 250,000 people in Washington DC, as well as millions of Americans who watched him on television.

After reading from his notes, towards the end of his speech King “wandered off his text”. It was a turning point in the speech, writes Taylor Branch in ‘Parting the Waters. America in the King years 1954-1963’. King had to decide whether to go back to his notes, or improvise the most important speech of his life.

Knowing that he had wandered completely off his text, some of those behind him on the platform urged him on, and Mahalia Jackson piped up as though in church: ‘Tell ’em about the dream, Martin.

Taylor Branch, p. 882

The rest, as we say, is history. King improvised the rest of his speech, drawing on bits and pieces of sermons he had delivered in the 15 years leading up to this moment. In a 1999 poll among scholars, ‘I Have a Dream’ was ranked the top American speech of the 20th century.

This begs the question: where did King acquire his powers of persuasion? And what lessons can we glean from him?

In some ways, King was predestined to be a persuasive speaker: his father was the most influential preacher in Atlanta. But King didn’t rely on natural-born talent alone; he was a serious student of the art of persuasion.

According to Taylor Branch, he was heavily influenced by Robert E. Keighton of Crozer Theological Seminary, a professor in homiletics (that’s the science of sermon preaching):

Keighton (…) emphasized that a large part of religion was public persuasion (…) King came to accept the shorthand description of oratory as “the three P’s”: proving, painting and persuasion, aimed to win over successively the mind, imagination and heart

Some further digging in obscure handbooks for preachers and ministers made it clear that Keighton, in turn, was a pupil of a Halford E. Luccock, writer of In the Minister’s Workshop. It’s a classic manual for preachers, and devotes a full chapter to sermon preaching.

And—like I suspected when I went hunting for his book—Luccock’s writing is uncannily relevant to content marketing, inbound marketing and thought leadership.

(Note: I replaced “content” for “sermon” everywhere, and “writer” for “preacher,” to make it more applicable for marketers and to make it easier to read.)

1. Beware of pancakes

The worst kind of content is what we scientifically describe at FINN as pancake writing.

It’s content that starts in the middle of a subject, that lacks a plot or direction and kind of expands outward as the author feels their way around the subject. Luccock already warned preachers about this some 60 years ago: content should always be on the move, he says.

Content should move along straight lines rather than revolve in circles around the same spot.

Halford E. Luccock

That’s because people will always turn their attention to movement. We can’t help it—it’s how we’re wired:

People’s attention will follow a thing as long as it is moving; when it stops they relax, as though the plot has sagged.

Halford E. Luccock

Pancake writing doesn’t move—rather, it oozes, until it finds it final form, by accident rather than by design. Do your readers a favor and save pancakes for breakfast.

2. Where should it move? Towards an assigned goal

So where should your content move?

This is the billion-dollar question indeed. It is the hardest question of all, but it should be answered before you start writing. You need an assigned goal for your content, as Luccock calls it:

Effective content is marked by progress; and progress is impossible without structure. Progress includes movement, but (…) it is strategic and cumulative movement toward an assigned goal.

Your content is much more like a drama than it is like a novel. Many a novel has been begun with the author having his characters and main situations in mind but without final decision in detail about how it is going to come out. (…) But with a drama, the author must know the end from the beginning. He knows that Hamlet gets killed in the last act.

Planning in advance will also avoid the trap of getting lost in your own writing. This is more common than you think. Often, a subject will seem promising and rich, but you realise during the writing process that even though you can describe it, you don’t have anything meaningful to add.

As Luccock says:

A subject is like a greased pig. It can slip through the hands with incredibly elusive wriggles.

You can avoid this if you force yourself to make an outline. A good outline includes the headline (title) you will use, what your main points will be and precisely what conclusion you will draw.

Before you have this outline, you shouldn’t be writing at all—you should be thinking about your outline, finding facts to prove the points you want to make or checking those facts that you and others accept as truths.

These accepted truths usually turn out to be only half-truths. That’s not a problem; on the contrary, it will offer you something surprising to add to the debate. “You know that fact that is accepted as a truth? Here’s the problem with it…”

The key lesson here is this: spend less time writing, and more time researching, thinking and double checking your assumptions. Armed with facts and insights, you will find it a lot easier to define the assigned goal that Luccock discusses.

3. Find new ways to formulate accepted truths

Once you have your assigned goal, spend some more time thinking about how you can make it sound great.

One of our favorite quotes about content marketing is from a paper from the seventies in which Murray Davis formulated a theory of interestingness (PDF). He said, “Great scientists are not considered great because they are right.”

Great scientists are not considered great because they are right, but because they are interesting

Murray Davis

Freud and Marx got it wrong about a lot of things, but they are still studied today. Why? Because they were interesting.

In content marketing and thought leadership—as in preaching—it’s very hard to find radically new ideas.

Most of the time, you need to find a new, surprising way to formulate an existing and accepted truth. Luccock advises a technique he calls “fruitful revision.”

In essence, fruitful revision is the habit of constantly asking yourself, what is the most distinctive way to state this truth? What image, what analogy, what argument—or, even, what outrageous comment can I come up with to state my truth?

The takeaway here is, again, think more, write less.

4. And while you’re at it, tell the reader where he is, too

Now that you know where you’re going, do your reader a favor and let them know too as you’re writing it down. Says Luccock:

A piece of content is not a maze. It is more like a highway well posted with legible signs indicating: this is where we are now; the next place will be so and so.

This may be stooping to a lowly service, but it does serve the traveler in a way that no eloquence alone could match.

Luccock mentions the word “service” here. This is exactly the way to think about content marketing: it should have added value for the reader. Content serves a purpose beyond your self-expression. (If self-expression is what you’re after, write poetry.)

5. Your content should have an emotional outline too

Now moving into the more advanced stuff: think about how your audience will feel as it reads your piece.

There is also what might be called a psychological outline that must be kept in mind, one that takes account of the emotional rhythm of the audience.

Rest an audience occasionally, to give it a breathing spell, so that it can come back to move along with renewed vigor.

This is where your readers should say ‘Amen!’”

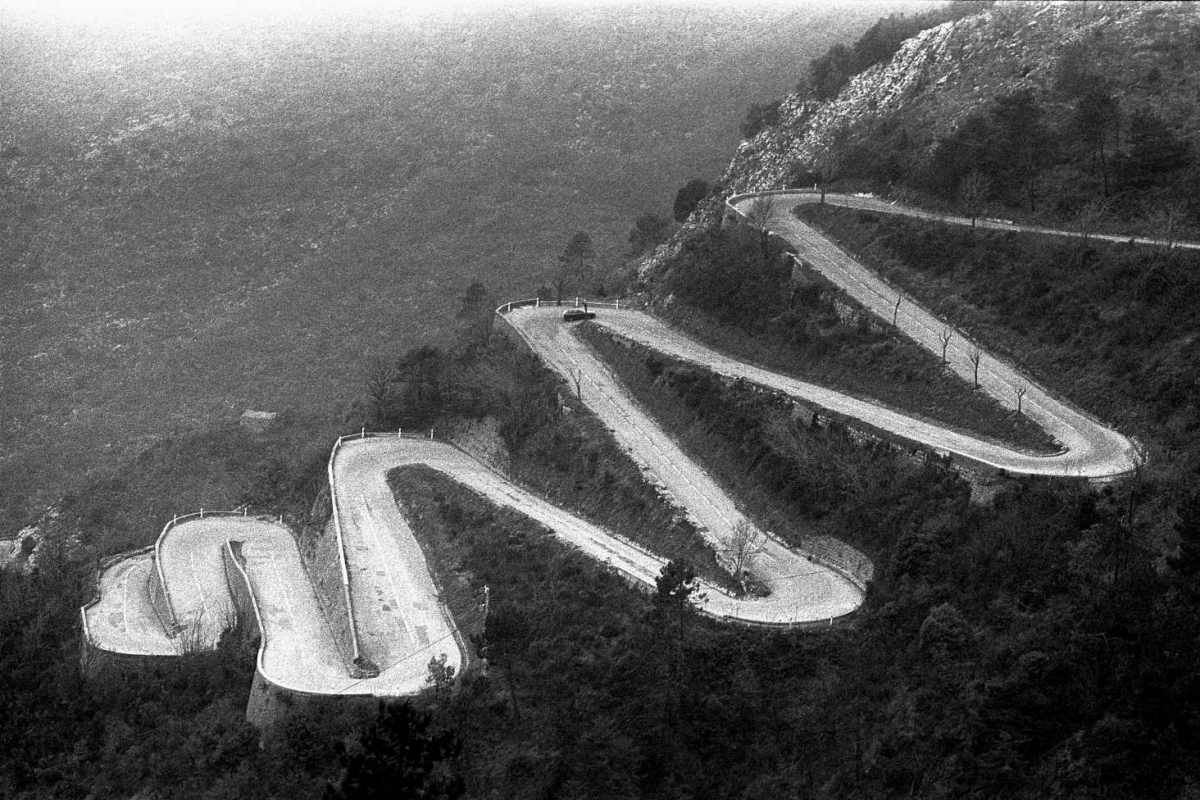

In my mind, a great article or blog post looks a bit like this:

It has twists, turns, excitement and surprises—it’s a little challenging at times but you know that this is actually the most efficient way to reach the summit.

6. Go deep instead of wide

Finally, keep your subjects small and deep rather than broad and shallow:

One general observation applies to most content. The most helpful content is usually one which teaches in detail on a limited area rather than one which travels, no matter how eloquently, over a wide stretch of territory.

I don’t know about you, but I found it mind-blowing that a mid-20th century specialist in sermon preaching would offer such awesome advice on content marketing.

But wait! There’s more.

Luccock didn’t merely give theoretical advice. He also helpfully defined about a dozen content structures that feel remarkably contemporary. In fact, I took the content types that seemed most useful to marketers in this blog post, and I included some present-day examples of journalists and bloggers using these exact patterns for their content.

Type 1: The Skyrocket

As a storytelling technique, this is probably one of my favorites.

[The Skyrocket] begins on the ground, rises to a height, then breaks into pieces and comes down to earth again, often in red, white and blue stars.

Huh? Okay, let’s try again:

It begins on the ground, in real life—it travels up to a [higher] truth which has meaning for that situation; and then the content comes down as it were, in separate divisions to that situation.

Here’s an excellent example from Vox recently that follows the pattern:

This is what happens in the video:

- Begins on the ground: “I hate this door.”

- Travels to higher truths: “Apparently I hate it because of bad design. Design is important.”

- Comes down to earth again: “It turns out that you can improve every functional object in the world by applying principles of good design.”

It can get slightly didactic as a form, but it’s a very persuasive way to introduce theoretical concepts to your readers and to prove the relevance of these concepts in their professional or private lives.

Type 2: The Chase

Much harder to pull off is The Chase. But it’s a beautiful narrative form, and one you should master if you want to write compelling long-form content.

The Chase is like a collaborative hunt set up by the writer with his audience. It’s about “getting an audience to explore a problem and pursue a solution rather than merely announcing the result to them.”

In other words, it’s a whodunit.

The chase is a whodunit – great to keep audience’s attention (but hard to pull off)

A Chase is a great way to keep the attention of the audience, because the audience is actively involved in the hunt. As they are reading or listening, you’re inviting the members of the audience to think about the problem, to guess at answers, to formulate hypotheses and see them validated or disproved.

Malcolm Gladwell is probably the master of this kind of storytelling—always teasing the next little insight, the factlet that changes the direction of the narrative, the counterintuitive event that disrupts the narrative flow. (You can read all Malcolm Gladwell’s New Yorker articles here).

Another great example is this circa 50,000-word blog post over at Wait But Why. It’s a very, very #longread about the question: Where are all the aliens? It’s incredibly geeky, and oh, did I mention that it’s long? And yet, it manages to keep the reader engaged throughout.

Here’s the outline of the piece:

- Where is everybody (everybody being “intelligent alien life forms”)?

- Well, maybe there is nobody else, because intelligence is rare and we’re alone in the universe

- OR! Maybe we’re just the first species to reach intelligence and we’re ahead of all the others

- OR! Maybe there were others, but they’re all dead by now (oops!)

- OR! Maybe there ARE others, but we just don’t notice them because they are so far ahead of us, they actually live in different dimensions than we do

You get the idea.

Setting up a Chase is hard work, because it requires every ounce of your storytelling talent. It’s highly effective at making an audience feel (rather than understand) that a problem or a subject is important and deserving of their attention.

(After reading about the Fermi paradox, I admit I got slightly more worried about the fate of all those aliens out there.)

Type 3: The Jewel

Somewhat related to the Chase, the Jewel involves

Turning one idea around as one might turn a jewel in his fingers, allowing different facets to catch the light, and throw it into different realms of experience. Its usefulness consists in unity of theme, with diversity of relationship and application.

The Jewel structure works if your audience already cares about your subject matter. You are writing not to persuade them to care. You are writing to help them think, which is easier than getting them to care about a topic that they didn’t know about.

The Jewel works if you want to help your audience think about something they already care about – rather than care about something they don’t know about

In other words: while a good Chase gets you worried about the fate of the aliens, a Jewel will serve better once we’ve actually found us some aliens and we’re wondering how to approach them.

Type 4: The Classification

This: “10 types of people you meet at conferences”

I’m not a huge fan, although Luccock is. He says,

This process of classification has a sure interest because it has deep roots in the nature of the mind, as developed throughout history.

He probably has a point when he says that you can be sure to hold the interest of the audience when you start your story by stating that “there are four ways to act in this situation.”

Naturally, your audience will want to hear all four of them.

Type 5: The Roman Candle

Related to the Classification. The Roman candle is a kind of firework that “throws out sparks for a few seconds, then throws out a ball, then more sparks and another ball.”

Luccock didn’t have gifs to illustrate a point, but happily we do:

Today, Roman candles are known and loved as…listicles! Luccock even predicted the rise of BuzzFeed when he suggested that the listicle could be a good structure for a sermon titled “If I were 21 again”!

Here’s proof: “16 Things We Wish We Could Say To Our Younger Selves”.

Like I said: these preachers were marketing visionaries.

A final piece of content marketing advice: on “grip”

Finally, there was a fascinating new concept that I encountered while reading about advanced homiletics, and it’s a concept that applies equally to content marketing and thought leadership content. It’s called “grip.”

This is how it was defined by Martin Luther King Jr.’s contemporaries:

Grip is a term to express that manner of writing or speaking which impresses a hearer with a strong belief that the writer feels that he has something to say that is worth saying, and which ought to be said.

Grip is what

carries the mind away from the speaker to the thing spoken. It is obvious that the effect of content ought not to be admiration for the writer, but a sense of having read something which one will never forget.

Stand up not because you have to say something, but because you have something to say. Make sure of that first. Then say it.

Martin luther king, jR.

And here’s one piece of advice to print, frame and hang above your bed:

Grip is prerequisite for every writer who would fulfill the counsel that a writer should ‘stand up not because you have to say something, but because you have something to say. Make sure of that first. Then say it.