Which crises receive the most media attention? That question is important in crisis communication, because it is primarily media attention that makes or breaks your company’s reputation (see our blog on reputation).

And while a crisis within your own organization always feels like “do or die,” to the outside world and media that is not necessarily the case. Some crises hit companies at the heart of their reputation; others slip by almost silently.

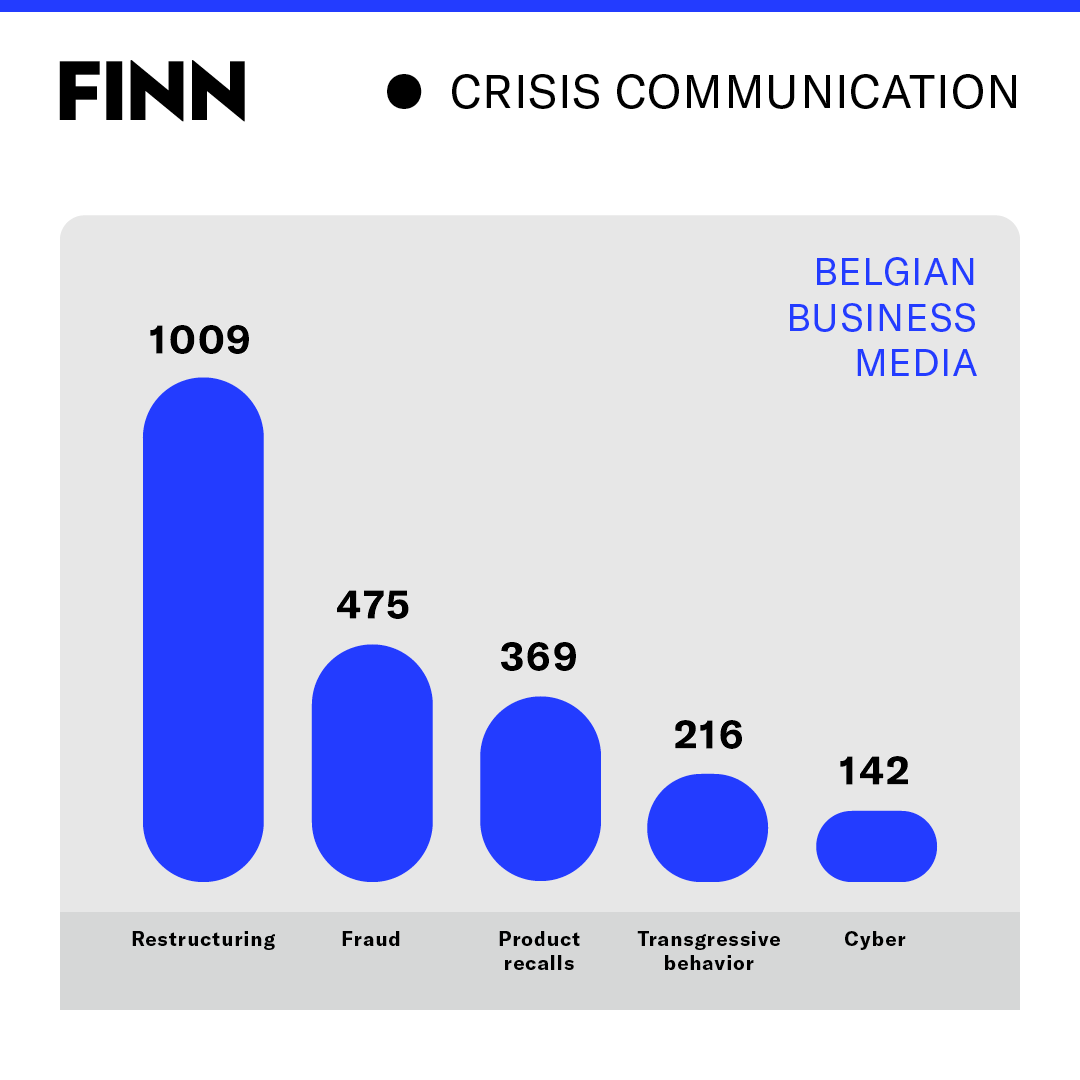

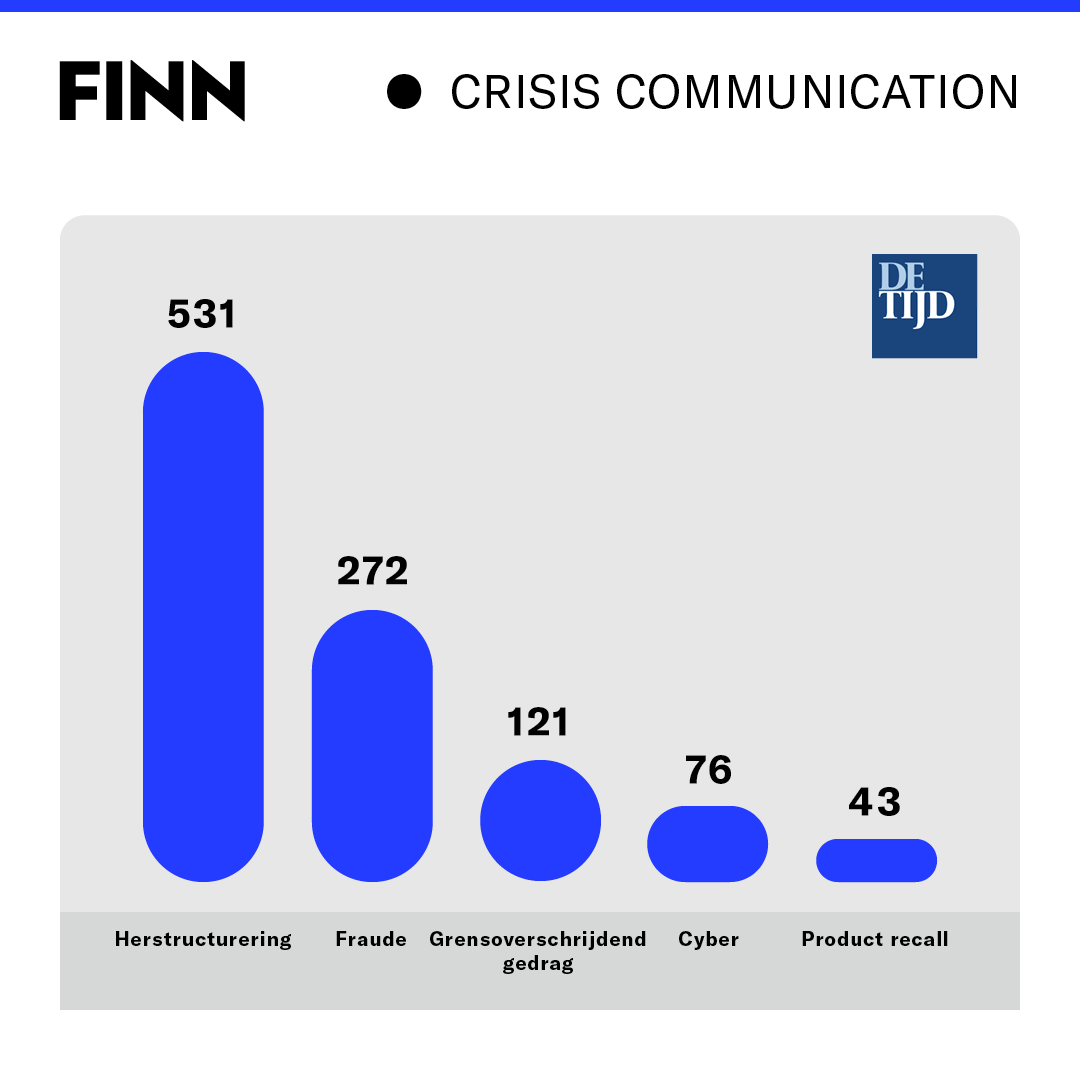

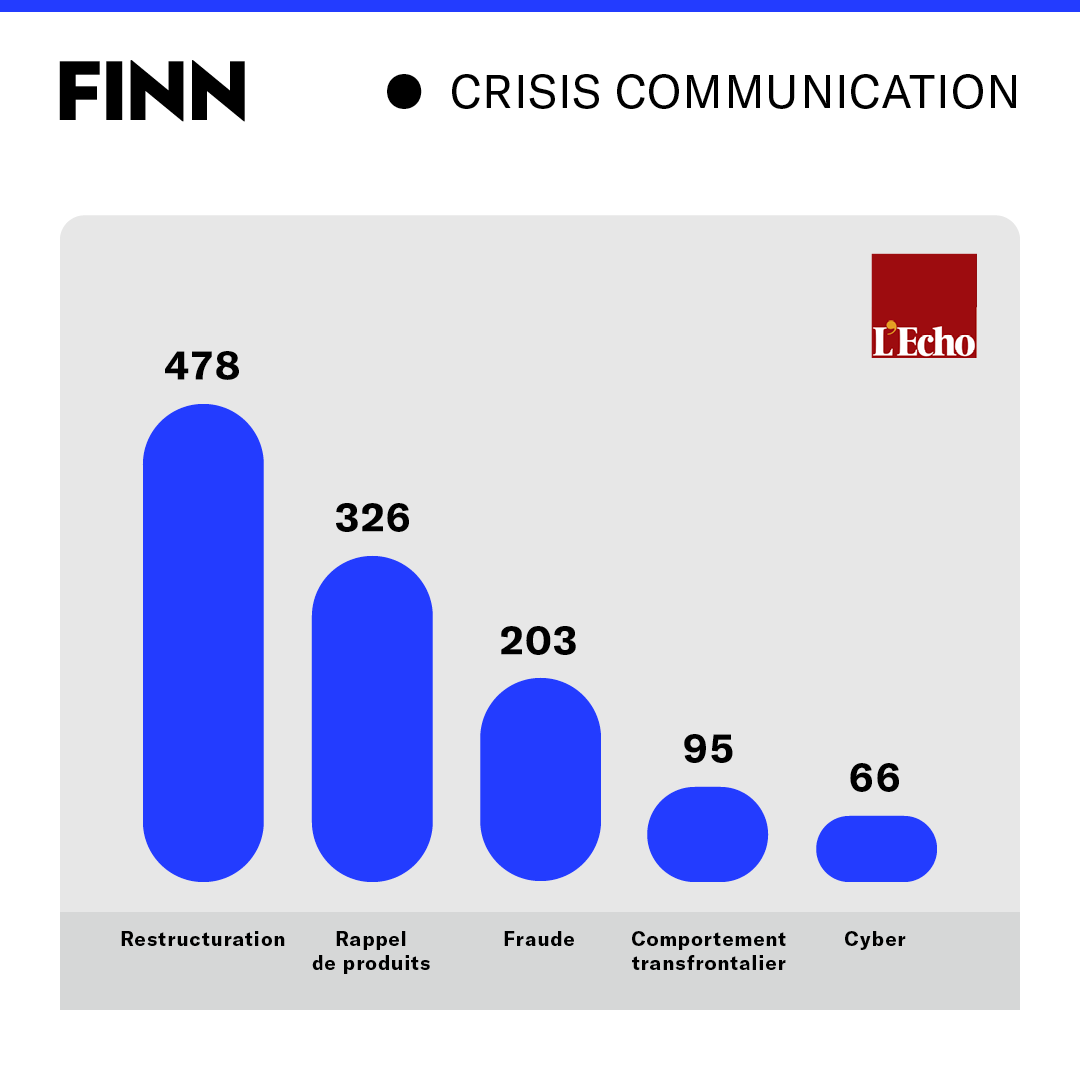

For the first time, we investigated which types of crises receive the most attention in the Belgian media (*).

In our research, we examined different clusters of crises:

- restructurings: layoffs, closures, strikes, Renault Act

- product recalls and other product defects

- fraud: embezzlement, usury, malpractice, tampering

- transgressive behavior: including #metoo, bullying and harassment

- industrial accidents

- cyber incidents: ransomware, hacking, data breaches, phishing,….

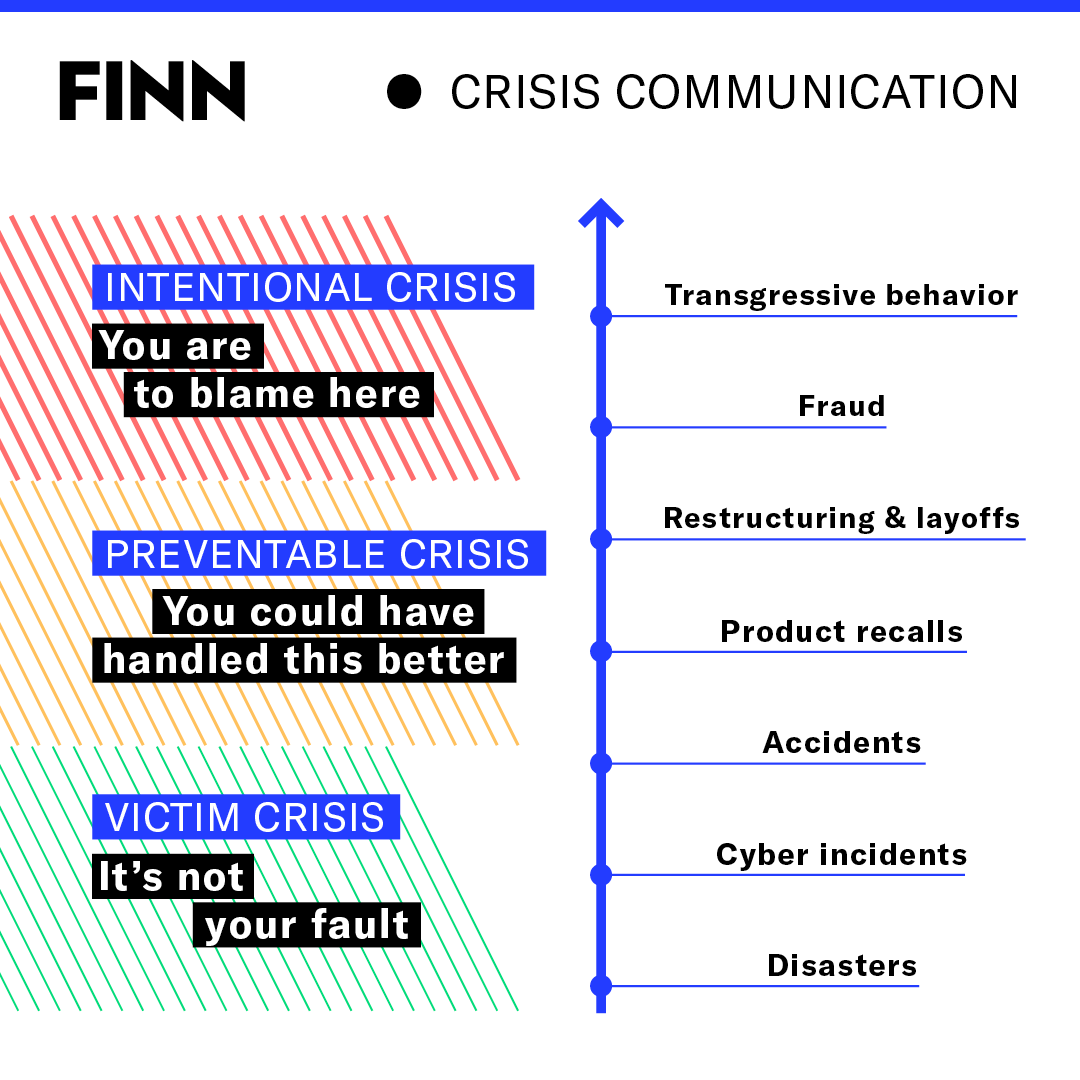

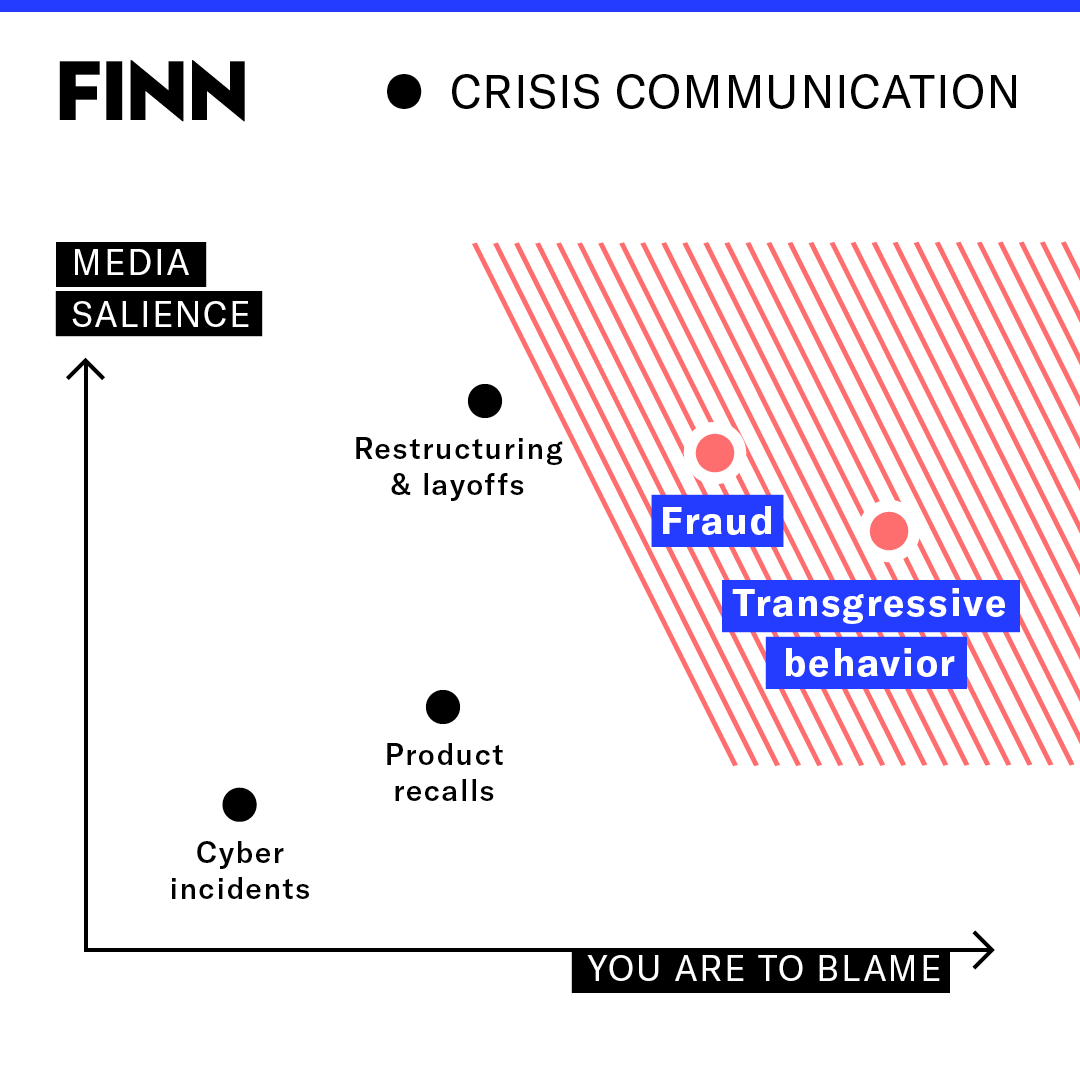

We then looked up in (*) De Tijd and L’Echo how often this type of crisis appeared during the last 12 months (the so-called “salience” of crises), and to what extent companies are “blamed” for this type of crisis (“attribution“).

These are two very important factors for communication professionals to predict the impact of a crisis – and thus to get their crisis communication response right.

Crisis communication in Belgian media: how common are crises?

1. Restructurings

Restructurings receive by far the most attention in media, both in our Dutch-speaking and French-speaking sample.

Last year, almost 3 articles a day were published in De Tijd and L’Echo on restructurings and strikes. Good for a total of 1009 posts in one year’s time.

This included the big tech layoffs and the strikes at NMBS, De Lijn and Ryanair.

Previous research by FINN already showed that a collective dismissal (“Renault Act”) becomes newsworthy very quickly, as early as dismissal rounds of 20 to 30 people. Very often this makes the news through regional correspondents, after which the news is picked up by national editions and then by news agencies like Belga or larger national media.

Restructuring and strikes should therefore be a fixture in any crisis communication plan.

Restructurings are also salient because they often create a conflict situation. Companies must negotiate a social plan with unions, and unions (sometimes aided by politicians) will try to do maximum reputational damage to force greater concessions in the social plan.

Communication around restructurings and collective layoffs receives a lot of attention at companies, and rightfully so.

To what extent companies or management are “blamed” for restructuring varies widely: from fairly neutral to somewhat frowned upon. Getting the narrative right is thus very important in these cases: companies must credibly demonstrate on the one hand that the crisis was inevitable (“victim” crisis), but on the other hand – and equally credibly – express their faith in the company’s future.

2. Fraud

Fraud cases are also quite salient, according to our research.

This was rather surprising. Fraud, embezzlement and tampering are usually addressed in a crisis communications plan, but are not always top of mind. Most companies assume (correctly) that their employees have integrity.

But for media, these stories are naturally very interesting. That’s why individual stories about nurses committing thefts or bank employees embezzling small sums from customers become just as interesting for media as multi-million dollar embezzlement cases.

3. Bullying and #MeToo

Transgressive behavior receives a great deal of attention. Very often they become not just news stories, but also fodder for the op-eds and columnists – increasing the reputational impact of the crisis.

This fits in with a social trend in which well-being is becoming more important, and in which the responsibility for the well-being of employees is placed on the employer.

In our opinion, this is still not given enough attention in companies’ crisis communication plans. It’s important to understand that media very quickly look at the top of the company in cases like these. Media are quick to ask “what did you know and when did you know it?” and are quick to blame top management even the board of directors for bullying and transgressive behavior, because it is widely accepted that the culture of an organization is created at the top.

Some of the questions media and other stakeholders will ask:

- Were there previous complaints?

- How did the company handle those complaints?

- How did the company deal with the person making the complaint?

- What culture does top management itself set (have there been complaints against top management itself)?

A crisis around transgressive behavior can very quickly become an oil spill – and one that is highly flammable.

4. Cyber crisis

Data breaches and cyber incidents are among the most common incidents for organizations worldwide. Operationally, they also have a very severe impact: companies can sometimes be down for weeks due to ransomware, for example.

But: for media, they are actually less interesting. There is often not much to report about them – IT systems are unknown territory for journalists, and companies often do not know how a problem was caused, or do not want to communicate about the root cause of the issue even if they know it.

In terms of attribution for the crisis, cybercrises fall into the category of “ambiguous crisis situations,” where it is not always clear who is responsible.

Research shows that when cyber crises occur, companies often take on the “victim role” and often get away with it. In some cases, companies do have to admit that their security systems or prevention were inadequate. (Kuipers & Schonheit, 2022)

Lately, we do see a shift in how stakeholders look at cyber incidents. As IT journalist William Visterin accurately noted, outsiders are less inclined to blame companies for ransomware:

Where reactions towards afflicted companies used to tend towards pity (“how careless/sloppy have they been?”), today there is more understanding. Today there is a general awareness that such a cyber-attack can happen to anyone. That was not the case a few years ago.

William Visterin in Computable, 2023

In Belgium, news coverage over the past year focused mainly on the cyber attack on the city of Antwerp. In Wallonia, there was also coverage of hacker collective Plays.

5. Product recalls

Finally, product recalls are an evergreen.

Almost every consumer brand will face a larger or smaller recall at one time or another – due to errors or defects in raw materials, production errors or mislabeling.

For journalists, these are important stories because they are “public service announcements,” a category irresistible to media outlets.

Think of the news items about stormy weather (“stay indoors“), sunshine (“don’t forget your sunscreen“) and strikes (“avoid the Brussels Ring“). In the context of product recalls, that becomes “don’t eat, return the item to the store.”

Coverage of product recalls is strikingly more common in L’Echo than in De Tijd. Whereas De Tijd has 43 items in one year, L’Echo has 365.

Attribution in recalls depends heavily on the circumstances. Recalls are often used as a crisis response strategy and, as such, may just improve a company’s reputation.

But: in some cases the company does get blamed for recalls, for example, if it turns out that a producer already ignored some food safety warnings, or that the company reacted too late when it learned of problems, or if the impact of the crisis was very severe (deaths or injuries). (See also Yakut, 2018)

What does this research mean concretely for companies? We list some tips for getting started concretely with the results of our research:

1. Create (or update) your crisis communication plan

Although only about fifty percent of companies have a crisis communication plan, it is clear from the above that some types of crises can severely damage your reputation.

There are also new trends ( transgressive behavior and cyber) that mean some plans may need updating.

Insights about media impact of certain crisis types can help you better assess and prepare for some risks. For example, fraud crises get much more media attention than companies may estimate.

Fraud cases – even small ones – get much more media attention than you think

A full-fledged crisis communications plan includes a “chain of command” to call out the crisis, a division of labor with contact information (as well as a backup per function), validation and reporting processes, a stakeholder matrix, various scenarios of common or foreseeable crises, and an overview of documents to be used in times of crisis, such as a template for a holding statement.

2. Work on your track record (“bolstering”)

A number of crises are strongly blamed on companies, such as bullying and fraud, but in certain cases also issues such as (food) safety and cyber security.

As a company, you can never rule out an employee crossing the line. What you can do is build a track record as a company that is committed to prevention and culture, so that you can rely on it later. This can be done through certificates (ISO, “Best Employer,” etc.) but also through internal and external communication.

Work on a positive track record today – so you can use it on a rainy day

In crisis communication, this is called “bolstering.” It allows you to say in crises, “Despite our strong processes around security, hackers still managed to…” “We have had a policy around transgressive behavior for ten years, but unfortunately we have to conclude that someone still…”

A positive pre-crisis reputation acts as a buffer against reputation loss during a crisis. Fombrun’s sees six aspects in which companies can build reputation: financial, emotional, social, work environment, vision and leadership, and products and services. During a crisis around one aspect, the other five aspects will “protect” the reputation from damage. (Fombrun, 2000)

3. Practice your crisis communication plan

A crisis communication plan is not enough.

A crisis communication plan serves primarily to support the organization in crisis preparation and to guide exercises around crises. It is not meant to be leaned on during a crisis – the first thing to go out the window in a robust crisis is management’s time and bandwidth to consult a manual. The processes and scripts must become an automatic process within the company.

So it is important to practice crisis situations with management and other stakeholders before they happen.

In crisis communication, it’s very much true that we don’t rise to the level of our expectations, we fall to the level of our training

Remember Achilochus’ famous quote, “We don’t rise to the level of our expectations; we fall to the level of our training.”

Contact us today for professional crisis communication plans or “dry run” training to prepare your organization for potential crisis situations.

Sources

Coombs, T. (2007). Protecting Organization Reputations During a Crisis: The Development and Application of Situational Crisis Communication Theory. Corp Reputation Rev 10, 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550049

Fombrun, C.J., Gardberg, N.A., Sever, J.M. (2000), The reputation quotient: a multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. Journal of Brand Management, vol.7, no.4, p.241-255.

Kuipers, S., & Schonheit, M. (2022). Data Breaches and Effective Crisis Communication: A Comparative Analysis of Corporate Reputational Crises. Corporate Reputation Review, 25(3), 176–197. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-021-00121-9

Visterin, W. (2023, 13 april). Visterin Fileert: De cyberaanval bij TVH. Computable.be. Geraadpleegd op 24 april 2023, van https://www.computable.be/artikel/columns/security/7493628/5658341/visterin-fileert-de-cyberaanval-bij-tvh.html

Yakut, E. (2018). Examination of Product Recalls In Terms of Attribution Theory in the Marketing Context: A Qualitative Meta Analysis. 10.18657/yonveek.350583.