In crisis communication, it’s exceedingly rare to be able to do a side-by-side comparison of crises. Like the famous Tolstoi quote that each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way, most crises are too idiosyncratic to compare them to other crises in anything but the most general way.

But a paper published recently in Public Relations Review by Roxana Maiorescu of Emerson managed to compare two reputational crises that are uncannily similar.

Facts: recalls at GM and Toyota

In the last decade, both GM and Toyota were faced with major recall actions. Toyota had to recall 5.3 million cars by January 2010 because of a “sticky gas pedal”. Despite 93 deaths and warnings to the top management about the problem, the company did not recall any cars until it was forced to do so following a government investigation into the problem. At GM, a faulty ignition switch caused 87 deaths, leading to 74 recalls that involved almost 27 million cars:

GM’s crisis started in 2005 when complaints from dealers and customers warned the company of stalls. Despite 87 deaths, GM labelled the warnings as a matter of customer convenience that only reached top management in 2014 (Valukas, 2014) when GM initiated major recalls and compensated the victims’ families.

While at GM the information about the faulty cars did not reach the leadership team, in Toyota’s case investigations pointed to the management’s purposeful avoidance of recalls despite warnings and 93 deaths all of which, in turn, enabled the company to save 100 million dollars. Finally, the company compensated the victims’ families and paid a fine of $48.8 million.

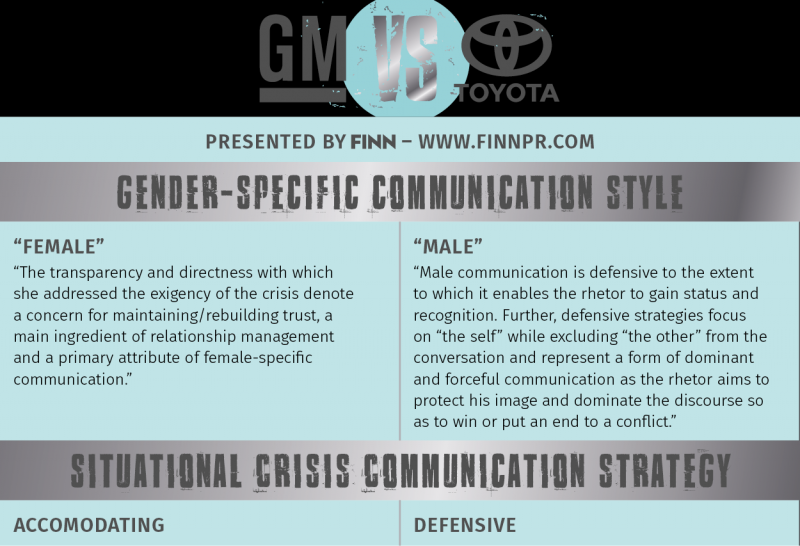

In her paper, Maiorescu compared the crisis strategy and messaging of both companies, as well as the media coverage and the reputational outcome that resulted from the two strategies.

PART I: GM and Toyota’s crisis response strategy

GM: a sense of urgency and regret

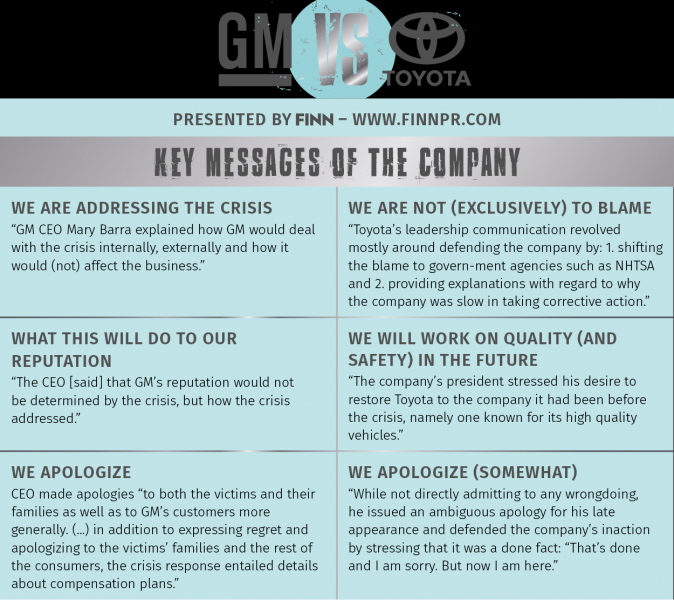

General Motors CEO Mary Barra has two main messages in her crisis communication: first of all, she expresses a sense of urgency to show that she understands that GM must tackle this crisis head on, internally as well as externally.

She also explains that GM ordered an independent investigation that would be made public:

Barra stressed the company’s full cooperation with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and Congress and mentioned that she had ordered an unvarnished external investigation into the company’s practices that would become available to the general public.

In terms of addressing the crisis internally, she emphasized the fact that her leadership team was not waiting for the final investigation to make changes in the company’s structure, bureaucracy, and culture but rather, such changes were underway.

Further, the CEO argued that she and the executive team were responsible for making things right and they were committed to doing so. A focus on GM’s current business operations represented the third pattern within the exigency theme, as the CEO asserted that, while addressing the crisis, the company continued to focus on its financial growth.

Interestingly, Barra says that GM’s reputation will not be determined by the crisis itself, but rather by the way GM deals with the crisis, which shows an intuitive understanding of the way media and the general public evaluate a crisis.

GM’s reputation will not be determined by this crisis, but rather by the way we handle it

GM CEO Mary Barra

The second main theme in Mary Barra’s communication is regret: “the CEO apologized and asserted that both she and the company deeply regretted the harm caused.”

Toyota: a defensive strategy

In contrast to GM, Toyota’s CEO Akio Toyoda’s crisis communication is foremost an attempt to defend his company:

“Toyota’s leadership communication revolved mostly around defending the company by: 1. shifting the blame to government agencies (…) and 2. providing explanations with regard to why the company was slow in taking corrective action.”

Instead of expressing regret or apologizing, Toyoda “issued an ambiguous apology and defended the company’s inaction by stressing that it was a done fact: ‘That’s done and I am sorry. But now I am here.'”

That’s done and I’m sorry. But now I’m here.

Toyota CEO Akio Toyoda

In defense of his company, the CEO notes that Toyota has strayed from being a company focused on quality to a company focused on numbers. He explains that he intends to restore the company to its former focus on quality.

PART II: Media coverage

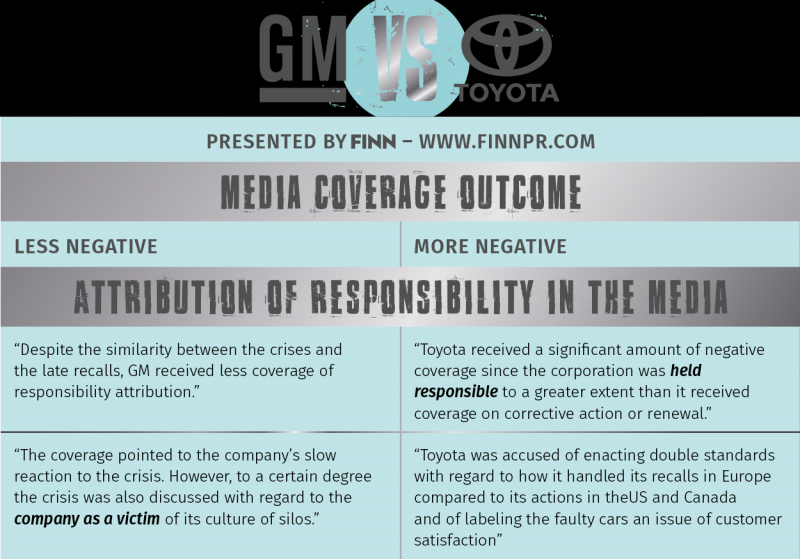

The result in the media is noticeably different for the two companies.

In the case of GM, most media coverage was devoted to the question of how GM would correct the crisis: how it would compensate victims, and how the external report would change the company’s culture and operating practices.

By contrast, in Toyota’s case most of the media coverage was about the question of who was responsible for the crisis – with most coverage blaming the company and criticizing its slow response to the crisis.

Also, the coverage dealt extensively with the question of how the crisis would (negatively) impact on Toyota’s reputation.

Toyota received a significant amount of negative coverage since [it] was held responsible

Interestingly, Maiorescu points out that, objectively, there wasn’t that much difference in how GM and Toyota dealt with the crisis when they first became aware of the quality problems:

It is important to note that GM’s crisis was similar since the issue of the faulty ignition switch was labeled as one of customer convenience. (…) However, despite the similarity between the crises and the late recalls, GM received less coverage of responsibility attribution.

And yet, Toyota was treated much more harshly in the media:

Toyota received a significant amount of negative coverage since the corporation was held responsible to a greater extent (…) Toyota was accused of enacting double standards with regard to how it handled its recalls in Europe compared to its actions in the US and Canada and of labeling the faulty cars an issue of customer satisfaction.

Key learnings

For us, this side-by-side comparison is an important validation of a crucial insight of Timothy Coombs’ Situational Crisis Communication Theory, namely: when choosing a crisis communication strategy, the number one priority should be to understand who the outside world will blame for the crisis.

It is entirely human to want to defend your company, find excuses or try to shift the blame to other parties. But it’s the role of the corporate communication director to challenge this knee-jerk reaction and to force the organization to take an outside-in perspective on the crisis. Some thought experiments that might help:

- If this would happen at a competitor, who would we blame? The company, or external parties?

- How would we explain this situation to a 16-year-old who knows nothing about our industry? How would they judge our responsibility in this case?

- What kind of proof would this 16-year-old (not a lawyer!) need to be convinced that we are not to blame? Do we have that kind of proof?

- If we send out this message, and the media contact any victims of this crisis, how will they react to our messages?

Epilogue

In March 2016, Toyota agreed to pay a $1.2 billion fine as part of a settlement with the US Department of Justice to end a criminal probe into the ‘sticky gas pedal’ issue.

The settlement, which amounts to more than a third of Toyota’s 2013 profit, is being called the largest criminal penalty imposed on a car company in U.S. history.

GM is still under investigation by Congress for the ignition-switch problem.

(Source: WaPo )

Sources

- Maiorescu, R.D. Crisis management at General Motors and Toyota: An analysis of gender-specific communication and media coverage. Public Relations Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2016.03.011

- Timothy Coombs, ‘Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing and Responding’