A few months ago, we blogged about the importance of network theory (“graph theory”) for PR professionals. New research, published last month, is another reminder how crucial this field is for PR today.

The paper shows how ideas or behaviors that are rare can actually appear very common to the friends of popular (well connected) people. And when ideas and behaviors appear popular and common, more people are inclined to believe the ideas, or try the behaviors out for themselves.

After reading this, you’ll never trust your Facebook feed again.

The activation treshold: how many lightbulbs does it take to switch on a random person?

Before we take a look at the findings of the study, let’s recap what network theory already knew about human behavior. It’s generally accepted that people take cues about how to behave from their friends, family and colleagues.

When a new behavior spreads to a certain percentage of our peers, it can reach an “activation treshold”, which prompts us to also adopt the new behavior. As scientists put it:

the activation treshold represents the amount of social proof an individual requires before switching to [a new behavior]

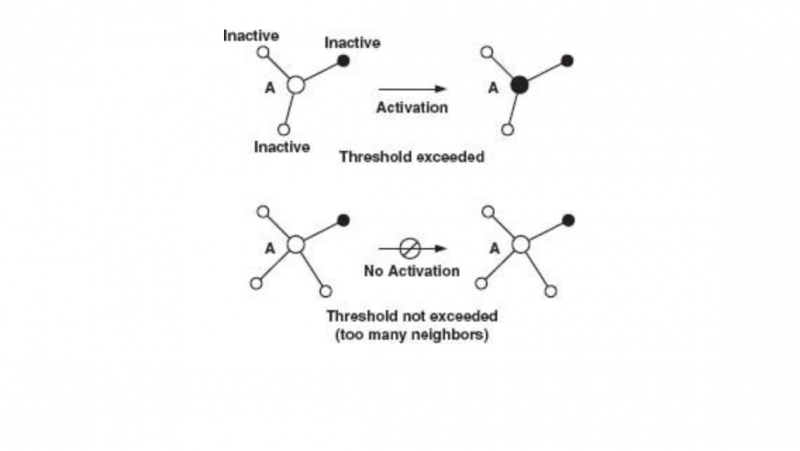

You can see it illustrated in this image, taken from Duncan Watts’ classic “Six Degrees”:

The behavior can be anything from “becoming a vegetarian” to “buying an iPhone”. Also, the activation treshold is not fixed. It can be very high or very low. For instance, if you want to convince people that they should start eating cockroaches, you’d better find a whole lot of people who can very persuasively praise the merits of a cockroach sandwich.

For other behaviors, the treshold is much lower – teenagers generally need very limited amounts of social proof to drink alcohol and party.

The importance of popular people

From earlier research, we already knew that popular people (people with large networks) are important to spread new behaviors, products and ideas. Since they they know a lot of people, large numbers of people are directly exposed to them and can take behavioral cues from them.

Highly networked people also usually belong to many different clusters of people.

“Some people act as bridges between different pockets of people, allowing ideas and behaviors to spread across the entire world”

See the red line in the graph below: it runs through the entire network, but at some points it has to pass through only a single node. Some nodes act as bridges between the different clusters. In much the same way, people can be bridges between different pockets of people, allowing ideas and behaviors to spread across the entire world.

Now, in the recently published paper, scientists found a third and quite baffling reason why popular people can influence other peoples’ behavior. A minority of popular people can seem to the world like a majority, because mathematics:

under some conditions, a large fraction of nodes will observe most of their neighbors in the active state, even when it is globally rare. For this reason, we call the paradox the “majority illusion.” The “majority illusion” can dramatically impact social contagions.

Reality distortion: a minority of popular people can look like a majority to their network

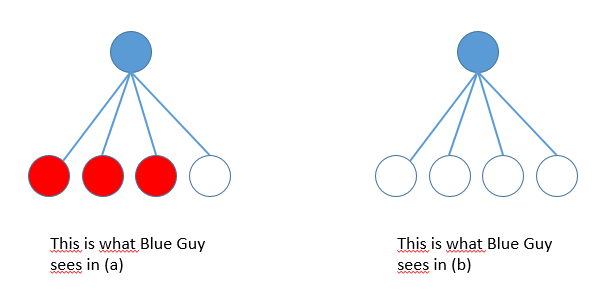

The best way to understand how the illusion works is to take a look at this schematic drawing of a small network of people. Every one of the nodes represents a person. The lines between the nodes are existing connections between the people.

Red nodes are “activated”, which means that have some kind of attribute like “has an iPhone” or “is pro gay marriage”. The white nodes are NOT activated.

To illustrate the point, let’s say the red nodes in the drawing are all fans of eating insects. As you can clearly see, they are definitely in the minority with only 3 out of 14 nodes (or 21 percent). And yet, every “white” node can observe that the majority of his friends is a fan of insects-as-a-meal, as you can see in this animation:

Why is this? Because people can’t see how the entire world behaves. We can only observe our own network.

So instead of observing that 3 out of 14 people like insects, the white nodes on the left are under the impression that a vast majority of people is into bug protein. Here’s how the world looks through the eyes of a typical inactive node:

It’s not a stretch to assume that some of our white friends on the left will try a roach sandwich somewhere in the not too distant future.

Now compare it with the image on the right: even though the same number of nodes are activated (3 out of 14), the inactive nodes don’t feel “outnumbered” here. Hold the roaches!

Yes, it happens in real life too

In some theoretical network models, the researchers found out, the majority illusion can kick in even when only about five percent of the nodes are active.

But the effect is not just a theoretical one. The researchers also found that the illusion can very well occur in real life.

We (…) examined whether “majority illusion” can be manifested in real-world networks. We looked at three typical (…) networks: the co-authorship network of high energy physicists, social media follower graph (Digg), and the network representing links between political blogs.

In real life, you need a bit more than five percent of the population to pull off a majority illusion, but it’s still quite powerful, it turns out:

The effect is largest in the (…) political blogs network, where (…) as many as 60%–70% of nodes will have a majority active neighbors, even when only 20% of the nodes are active. The effect also exists in the Digg network of mutual followers, and to a lesser degree in the HepTh co-authorship network.

Wag the dog, indeed.

This can cause people to think that an unpopular opinion or attitude is very popular, and adopt it as their own

This research has real world implications, the authors say – it can affect anything from the popularity of Taylor Swift to drinking problems.

the configuration of initial adopters on a network can systematically skew the observations people make of their friends’ behavior. This can make some behavior appear much more popular than it is, thus creating conditions for its spread

under some conditions, even a minority opinion can appear to be extremely popular locally

thus, if heavy drinkers also happen to be more popular, then people examining their friends’ drinking behavior will conclude that, on average, their friends drink more than they do. This may help explain why adolescents systematically overestimate their friends’ alcohol consumption and drug use

a behavior that is globally rare may be systematically overrepresented in the local neighborhoods of many people, i.e., among their friends. Thus, the majority illusion may facilitate the spread of social contagions in networks and also explain why systematic biases in social perceptions, for example, of risky behavior, arise.

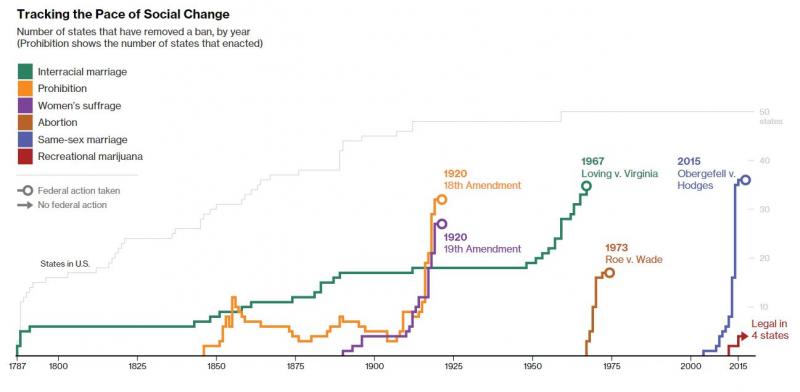

In fact, the authors say that in some cases of recent, seemingly dramatic shifts in public opinion (the Arab Spring and the support for gay marriage), it is theoretically possible that people didn’t actually change their minds dramatically. While not a very likely hypothesis, it could be that the underlying structure of the network shifted, giving us all the illusion that we were seeing a dramatic change in opinions.

(source of graph: http://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2015-pace-of-social-change/ )

What does it mean for PR?

In a way, this new research confirms most of our recommendations from the earlier blog post. But there’s a few nuances that are becoming a lot clearer to us.

1. Map your network better – create a true “organizational graph”

We said before that it was important to map the influencers, and map the influencers of the influencers.

This is more true than before. Study your influencer network. Develop a detailed “organizational graph” that maps every existing and potential stakeholder. This map should specifically take into account the size of the stakeholders’ network, and when we talk about network we mean both their online and offline network, naturally.

2. Build deeper relationships with your graph

It’s also becoming clear that creating relationships between your organization and your organization’s “graph” will become an important skill for PR professionals. And not just PR professionals.

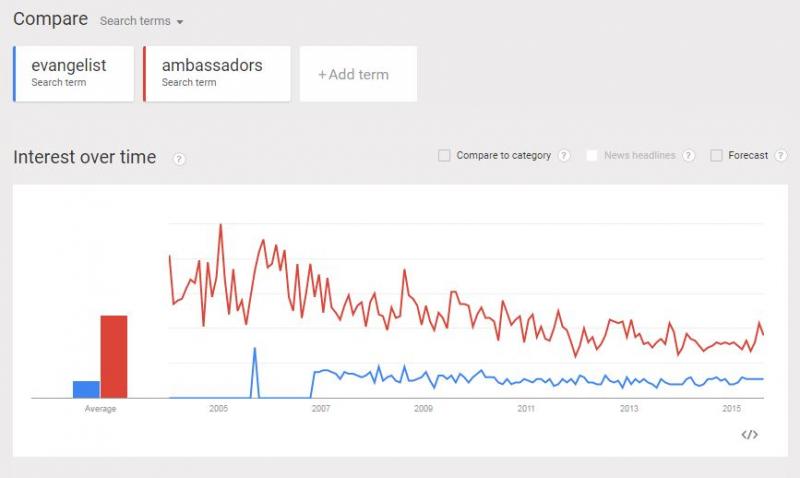

A big hurdle to effective PR programs we see in most organizations today is a lack of people inside the organization who have a mandate to engage in networking on behalf of the organization. This is an idea that we will develop further in one of our next blogs. After some enthusiasm for the idea that everybody should become an “evangelist” or “ambassador” a few years ago, we are not seeing it happen:

But if you want to “activate” an influencer, you not only need to know who the influencers are. You also need to convince them to “activate” themselves with your innovations, messages, attitudes or products.

Don’t forget that as you start seeding your innovation, you will be in the minority, trying to activate your stakeholders without much social proof. Your ability to switch influencers “on” will depend a lot on your existing relationship with them.

3. Values driven communication: decide why your message must spread through the network

Of course, an existing relationship will not be enough to activate these influencers. Your message, product or innovation itself also needs to be convincing in itself.

In an earlier blog, we discussed the reasons why people join online communities. Research showed that they are motivated in large part by values. People join these communities because the communities offer them a chance to express the values that they cherish.

It follows that people will be more likely to spread your message or innovation in their network if they feel that your message or your product rhymes well with their personal values and the so called character narrative that people tell about themselves.

In the organizational graph that we discussed, it will therefore be important to find a way to include information about the values and the character narrative of your stakeholders.

4. Develop a more rigourous approach to seeding

In our earlier blog, we indicated that flooding the graph was important if you want to reach the activation treshold. By “flooding”, we mean that you should try to activate as many people as possible nodes in your network at the same time. You want your message to light up your network like a Christmas tree, instead of hoping to have an impact by drip, drip, dripping your message into the world.

This new research underscores how absolutely crucial well executed seeding is in today’s world. You cannot create a majority illusion if your most important influencers do not push your content or product at roughly the same time.

In fact, we tested this approach recently, with surprising results. We wrote a blog post about the image of entrepreneurship on the Belgian public broadcast.

To seed the blog, we made a list of about 35 of well connected friends and sent them an e-mail via our stakeholder management tool getmustr.com with a link to the blog and with the question to seed the link into their network. A few minutes after we sent the e-mail (allowing them time to read the mail and the blog post), we seeded the blog on our own social channels.

We felt the message had the potential to be highly viral among our friends. Most of them were Belgian entrepreneurs, and advertising, PR and media people – people who had strong opinions on the subject.

We also knew that these 35 people were part of a very clustered community of Belgian entrepreneurs and influencers. We hoped that by activating all these influencers, we would be able to start a small “information cascade” in the Belgian entrepreneurship community.

And so it did. More than half of our friends posted the link on Facebook, Twitter or LinkedIn, but the impact of their seeding far exceeded our expectations: at the end of the day the blog was shared almost 1200 times on Facebook. The secret was: existing relationships, a message that resonated with the stakeholders and a seeding strategy that was built on timing.

We’re curious to hear your thoughts – let us know in the comments or give us a shout out on Twitter, Facebook or LinkedIn!