We were struck by this paragraph in a recent article in the FT about the PR troubles that Huawei is experiencing in the US and Europe:

From the 1990s, Huawei enlisted some of the most illustrious western consultants. (…) It also employed a vast array of global PR companies (…) But at crucial moments, the company did not heed their advice and even outmanoeuvred the consultants. “There was always a fundamental lack of trust (…). You offer guidance and are regularly second-guessed,” Mr Plummer said.

When mr. Plummer escalated an issue with non-compliance of trade sanctions against Iran to Huawei management, he no longer received a reply from his client – and eventually, he was shut out of consultations and decision making altogether, he says:

I received no response or reaction to the concerns I expressed and was effectively iced out of the loop,” he wrote, adding that he “had touched on topics that were off-limits.

The FT’s diagnosis is that the Chinese top management of Huawei lacked trust in their Western consultants. Implicitly the FT suggests that the company can’t or won’t understand its Western stakeholders and advisers.

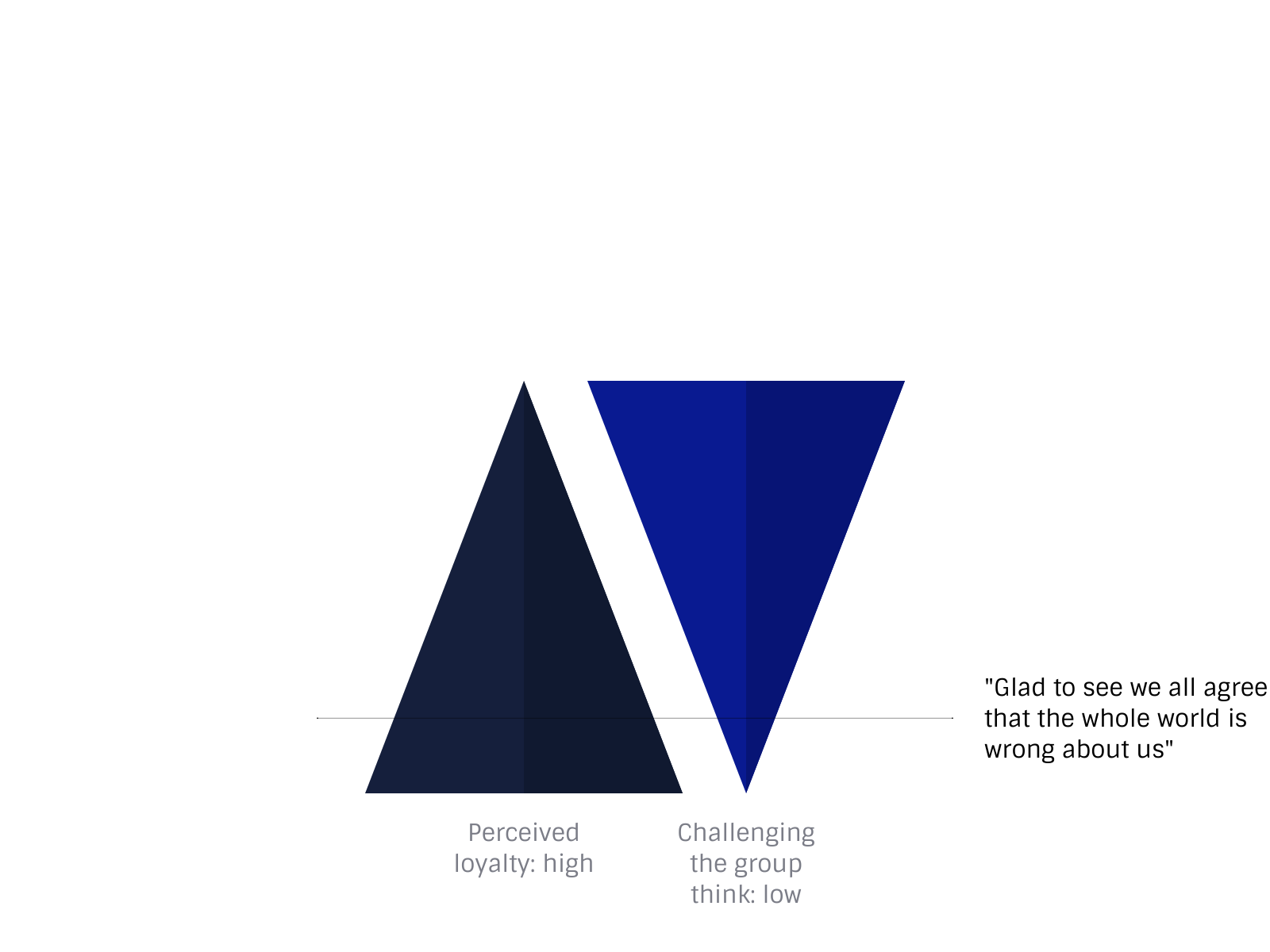

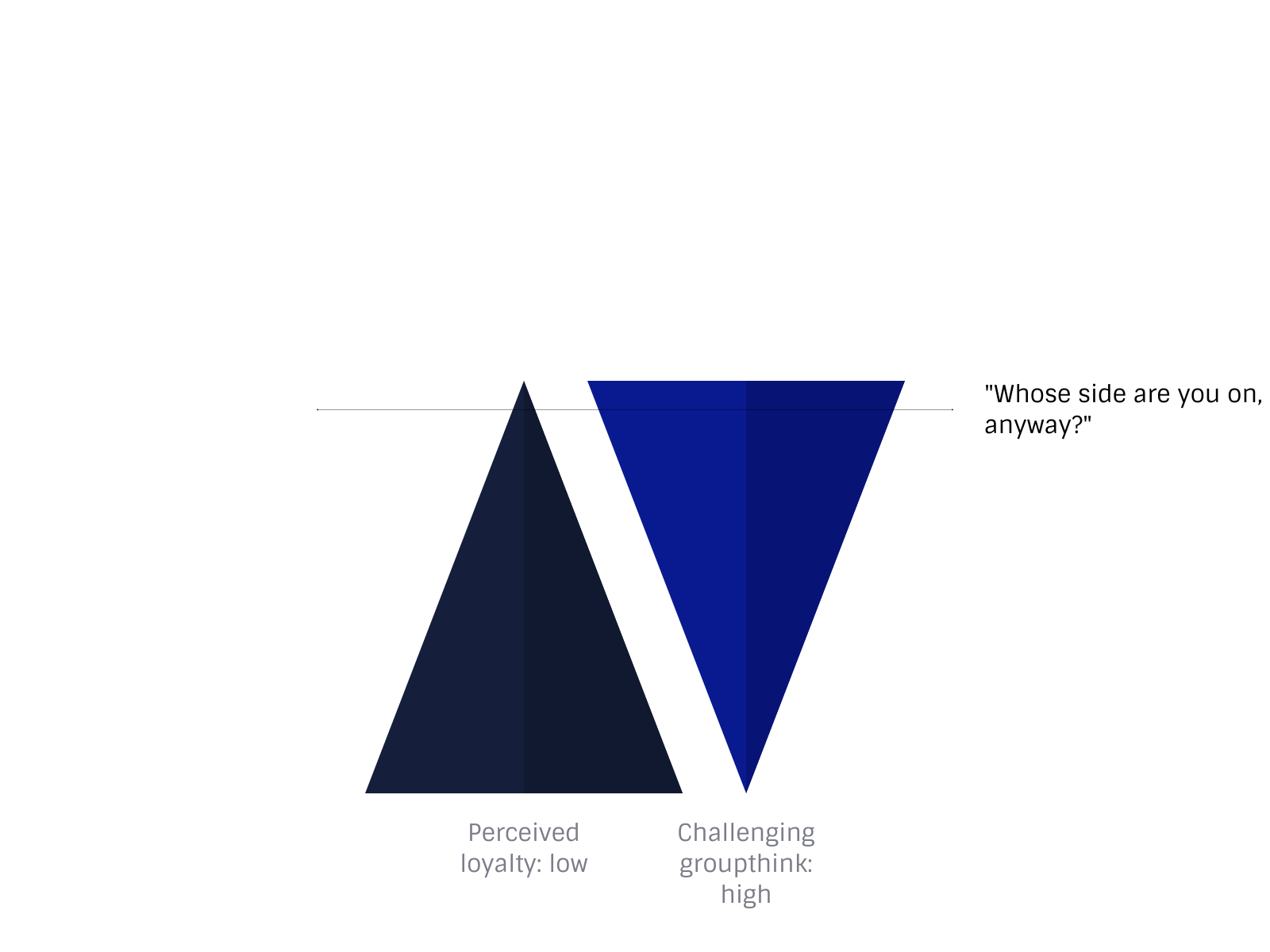

But we think every communication professional has had similar experiences – they occur in international organizations, but you can also run into it with local management teams. The issue as it is described here bears more resemblence to groupthink than to insurmountable cultural differences.

Groupthink and corporate communication

In the book “Groupthink”, author Irving Janis suggests that groupthink is especially likely:

- in organizations with a strong, charismatic leader

- where decisions are made by a group that is strongly cohesive (or, as we say in our profession, with a strong “corporate culture”)

- and where pressure from the outside increases the importance for the organization to offer the right response

It’s noteworthy that external pressure and internal cohesion are typical ingredients of issue management and crisis communication – and it does not come as a surprise for corporate communication practitioners that issue management and crisis communication are situations that have a high tendency to produce groupthink. And even if the leader of the organization isn’t strong or charismatic, in crisis situations we see that management teams are more likely to defer judgement to the CEO.

Add to that the pressure from the outside, which is sometimes considered excessive and unfair, which makes it even harder for the corporate communication department to offer outside-in perspective on the issues and crises. Here’s a few ways that groupthink manifests itself in crises and issues:

- Stereotyping: “media and activists are always against us anyway, whatever we do”

- Rationalization: “the outside world doesn’t understand the first thing about the problem”

- Self aggrandizement: “we do so many good things, why do they never talk about that?”

- Moral superiority: “we’re actually very ethical people”

- Peer pressure: “sometimes we have to make difficult decisions, and we can’t run away from that responsibility”

- Self censure: silence at times when a group decides to ignore important signals

(Raise your hand if you’ve heard any of these statements in meetings about difficult stakeholders)

How to avoid these situations?

1. Be pre-suasive

In his book ‘Pre-suasion’, Bob Cialdini discusses the art of influencing people before you need to exert influence. That’s an important principle for corp comm professionals.

If you’re forced to discuss basic principles of stakeholder management while the issue or crisis is unfolding – or about facts (like your reputational standing with outside stakeholders), then your chances of convincing a critical and senior audience are slim.

Work to create broad acceptance of principles of stakeholder management and issue management among C-level executives. The best way is to make sure that the following assets are in place:

- A formal corporate communication strategy

- Ideally, this strategy is based on an up to date issues and stakeholder mapping which is updated every quarter or at least every year – and which is discussed with top management. This mapping is the fastest way to bring the external perspective into a meeting.

- Up to date quantitative and/or qualitative research which measures the reputation of the organization in an evidence based way. This research must be known by top management as well. This way, relevant research can be referenced quickly: “What will our answer be if stakeholder X repeats their key message Y in the media?”

Create acceptance and knowledge about external stakeholders by regularly offering insights about stakeholders, trends and evolutions in strategic meetings.

2. Build confidence

CEOs consistently say that they are looking for communication advisers who can take on the role of “strategic partner”. Only then will you have the authority to bring up delicate matters internally – and be heard. It’s self evident that this starts with knowing and understanding every nuance of your industry and organization.

But also work on presenting yourself as a hands-on executive, who combines critical thinking with a high sense of loyalty towards the vision and mission of the company.

Needless to say, pick your battles. While stakeholders and issues are important, they don’t need to prescribe the path of the organization. Not every issue is a crisis. Not every stakeholder threatens the license to operate. Not every detractor of your organization is right.

3. Make it safe to discuss external stakeholder perspectives

Not everybody is as comfortable as you are, switching back and forth between stakeholder perspectives – it’s not their job, for starters.

So avoid being a threatening presence towards team members who are not used to – and are not comfortable – discussing what they might regard as “negativity”.

Use a clearly recognizable process to give voice to positions of detractors towards your organization. Use tools like the stakeholder and issues map and make it explicit that you are now speaking as the “red team”. If necessary, you can use some of the harsher critiques in a media training – with you in the role of a fairly critical and even aggressive journalist.

If necessary, take issues offline. When the pressure rises to take (non optimal) decisions, buy time. Agree that the final decision depends on a separate meeting where the decision will be stress tested for its impact on known issues and stakeholders. Explain that stress testing increases the chances that the organization will reach a strategically sound decision which offers optimal long term outcomes.

Buying some time allows you to create a Q&A which integrates external perspectives – which you can then discuss with colleagues and C-level.